Page 27 - Baofang Collection Imperial Ceramics, Christie's Hong Kong May 29, 2019

P. 27

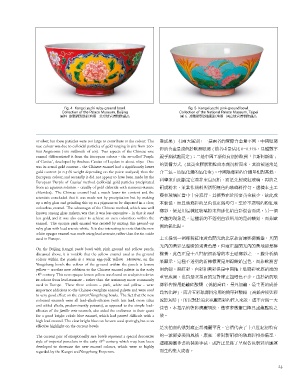

fig. 4 Kangxi yuzhi ruby-ground bowl. fig. 5 Kangxi yuzhi pink-ground bowl.

Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

எ୨ ᄮᾭᇙㅳ᪪⡚⎾ ࢈ᘢ༈ࢷ⁒㩴⻦ எՆ ᄮᾭᇙㅳ᪪⬄⬖⡚⎾ இ⛁ᘢ༈ࢷ⁒㩴⻦

or silver, but these particles were too large to contribute to the colour. The ⎉Ꮀ៧ ᝳݦഌࢥߣ厍Ӭᛓݦ⩢⎏༰㪡्㞖㞔Ӷऱ卿ԋஇ⇈⇶

rose colour was due to colloidal particles of gold ranging in size from 200-

ᆭ⎏्㞖㞔㙭׆ᙻ᪹ᰲ⇈⇶ ߿⩢㞒㞔ᬘ 卿ݰ㵲ᙇໃ

600 Angstroms (100 millionth of cm). Two aspects of the Chinese rose

enamel differentiated it from the European colour - the so-called ‘Purple Ԣ᳭㉹㿽⩧ 厎Հᛓԋஇ႙⻱ַᝳߣᙻ᪹ᰲǸࢽᙱ㩛ᙱ⡻ǹ

of Cassius’, developed by Andreas Cassius of Leyden in about 1650. One

⎏ㅳۄᙹᅴ ݯ㿩㞖⮈ₕ㯤⠄⯇᭢࠲ᮩ៝⩧卿ݯᵙ㘻ᛓ

was its actual gold content - the Chinese enamel had a significantly lower

gold content (0-0.31% weight depending on the point analysed) than the ्Հ᭞ ୨᭞ࢇ㣢⎏᭞ࢇ㞖 ǯԋஇ⇈⇶ᆭ⎏्㣢㞔⏟ཌ≾׆卿

European colour, and secondly it did not appear to have been made by the

☑ໝ།⊐᫉ᙷԆ㬳⯇ᮩ៝卿⩧ᛓݎㅳᎰ⡚⅘∇卿ݻཆԠ

European ‘Purple of Cassius’ method (colloidal gold particles precipitated

from an aqueous solution - usually of gold chloride with stannous-stannic ⒺᎰ⟾ថ卿Ԇ⋁ה㯭ᙠ⯝㘲ᚺὍⰰ⎏⇈⇶ᙠᐼࡵǯ㘺♎ទக႙

chlorides). The Chinese enamel had a much lower tin content and the

scientists concluded that it was made not by precipitation but by making ⻱ங⅘∇ࢎ⋁ԋࢦߎ᱁リ卿ݯܵࡥஙᙻᏒ㫬㿩㞖㖅ཐ卿ᘢ᫉Ꮀ

up a ruby glass and grinding this up as a pigment to be dispersed in a clear, ទ㖅׆卿⩧ӻ⇈⇶ᆭ⎏१ⰰԮᝤἃமࡵǯ⯍ᙻӶ㘲ᚺ⎏⟾⡚⇈

colourless, enamel. The advantages of the Chinese method, which was well

⇶ᆭ卿؝ᛓ⊇㘺♎⡚⅘∇⟾ថ⯝ⓕࢇ㠇⎊ᆭभ⩧ᎰǯऔӬٖ

known among glass makers, was that it was less expensive - in that it used

less gold, and it was also easier to achieve an even coloration within the ᝳ㑪⎏→㎜ᛓ卿㘺♎ᙲ⎏Ӷ㘲ᚺ⎊ᆭᏒ⊇⎏ᛓⓕ㝍㠇卿⩧㬳᪹

enamel. The opaque pink enamel was created by mixing this ground-up

ᰲ⎏᭘ࢇ㣢ǯ

ruby glass with lead arsenic white. It is also interesting to note that the new

white opaque enamel was made using lead arsenate, rather than the tin oxide

used in Europe. ӳᙔᓽߪӬ㱈⟾⡚㿩ⰰ㧷ݏ⎏࢈ᘢ༈ᄮᾭᇙㅳ⎾卿ݯ㧷

ݏݤ⎏㿩ᆭ१ᵐᜠ⎏⾰㿩ⰰḞǯֿ㫇᫈⎾㧷ݏݤ⎏㿩࣐ᛓᩏ

On the Beijing Kangxi yuzhi bowl with pink ground and yellow panels,

discussed above, it is notable that the yellow enamel used as the ground ᩄ㿩卿᫉ⰰ᫈ᛓࢦݨӽ⡕ߝᙲಫ⎏ទக⇈⇶ᆭԠӬǯᗌߎ៝⢙

colour within the panels is a warm egg-yolk yellow. However, on the ៧㰆▔卿㘺♎Ӷ㘲ᚺ⎏ᙲᩏᩄ㿩ᛓ⊇㣢㝍㠇१ⰰ卿⩧㬳᪹ᰲ⨶

Yongzheng bowls the colour of the ground within the panels is lemon

yellow – another new addition to the Chinese enamel palette in the early ⊇⎏㡗ǯ⟾⡚ᆭǮ⎊ᆭক㿩ᆭكᛓԋஇ㞏ӳ⇈⇶ᆭ།ᚉᙲ⎏

th

18 century. This new opaque lemon yellow was found on analysis to derive

㞒㇝Ꮀ卿Ԯἃᛓ᪖ᐽ㐈⎏㘺ཌ㫇᫈⎾ಫⰰӶཐǯ⊐ᙻᙲ⎏⇈

its colour from lead-stannate - rather than the antimony more commonly

used in Europe. These three colours – pink, white and yellow - were ⇶ᆭ⎐ᓚ⊇㠇㾪ⓝ㝍㾫 ׆㠇㵶ⓝ卿औം࠼㾪卿ᝬԖ㇝⎏Ꮀ֍

important additions to the Chinese overglaze enamel palette and were used

ἃ᭘ࢇ㟰 卿⩧㬳Նᆭ⇈⇶ᙠ⊇⎏➯ⓝ㝍㠇 㵶㠇ᝯײ⻤ᆭ

to very good effect on the current Yongzheng bowls. The fact that the new

coloured enamels were all lead-alkali-silicates (with less lead, more silica ᱁ᙻỌᜡ 卿Ꮢսཌᙻ㘤᭯ՙ㿃⻤ᆭ⎏ࢎ՞㊯卿㘺ӶἃӬഌ

and added alkalis, predominantly potassia), as opposed to the simple lead- צ㮥ǯទᐽ⎏⻤ᆭ᳖㿃ᚺሐ卿ۣ༯༯ᙇ✖Ⴁᥑݰ⊺䂆㿽Ԡ

silicates of the famille verte enamels, also aided the craftsmen in their quest

for a good bright cobalt blue enamel, which had proved difficult with a ᘤǯ

high lead enamel. The clear bright blue can be seen used sparingly, but as an

effective highlight on the current bowls. ᛓ᪖ᐽ㐈⎏㘺ཌ㫇᫈⎾⇷㿃⧎㏟卿ٛջヿԻࢦݨӽ⡕ߝ⁞ᝳ

The current pair of exceptionally rare bowls represent a special decorative ⎏Ӭ᰾ᇙ≢ㅛ㱈㰍ᡟ卿ᄮ㫇ՀႽཌᙲⒺ⎉⎏⇈⇶ᆭᓠۄ⯍卿

th

style of imperial porcelain in the early 18 century, which may have been

㘺♎⢨㿃അන⎏ㅛ㱈Ꮫᯧ卿Ꮅ㉓᫈ᛓἃԻ१→पⰰᙲᆭᏒ㙛

developed to showcase the new enamel colours, which were so highly

regarded by the Kangxi and Yongzheng Emperors. ⩧⊂⎏㫀ഌᎰ⩢ǯ

23