Page 47 - THE SLOUGHI REVIEW - ISSUE 13

P. 47

T H E S L O U G H I R E V I E W 4 7

This is reminiscent of the ancient Egyptians' hunting with the older type of Tesem (type

A, according to Brixhe). Were these “Salukis”, who hunted inside the gate, also fast

enough to have hunting success outside the gate, in the field?

In Angela Perri's article we learn about the

prehistoric dogs that were used for hunting [29].

As we already read in the title, these are dogs

beyond domestication, at least that is what is

suggested in the title. However, her

recommendations for archaeological excavations

are very much oriented towards modern questions

posed in the industrial age, which were not

necessarily relevant to early forms of

domestication.

“The use of dogs as hunting weapons represents a

first innovative step in human cognition, whereby

tasks previously performed by humans (or never

performed before) are transferred to animals. This

represents not only a novel innovation, but the

inception of a dynamic relationship between

humans and animals whereby humans harness the

innate properties of animals as technology (e.g.,

tools, weaponry, machinery), leading to their

ubiquitous use as modes of production (e.g., hunting,

transport, draught). This signifies an important

cognitive shift in regarding animals not only for

their material products (e.g., meat, bones, hides,

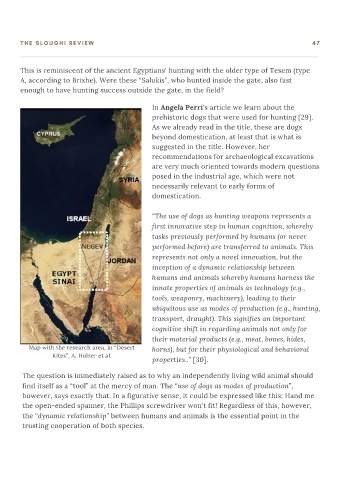

Map with the research area, in “Desert horns), but for their physiological and behavioral

Kites”, A. Holzer et al.

properties..” [30].

The question is immediately raised as to why an independently living wild animal should

find itself as a “tool” at the mercy of man. The “use of dogs as modes of production”,

however, says exactly that. In a figurative sense, it could be expressed like this: Hand me

the open-ended spanner, the Phillips screwdriver won't fit! Regardless of this, however,

the “dynamic relationship” between humans and animals is the essential point in the

trusting cooperation of both species.