Page 146 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 146

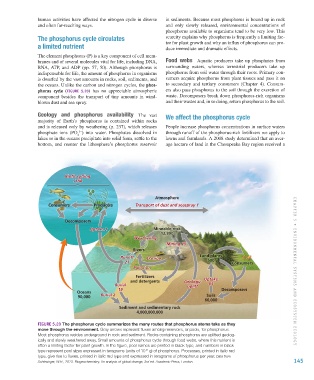

human activities have affected the nitrogen cycle in diverse in sediments. Because most phosphorus is bound up in rock

and often far-reaching ways. and only slowly released, environmental concentrations of

phosphorus available to organisms tend to be very low. This

The phosphorus cycle circulates scarcity explains why phosphorus is frequently a limiting fac-

a limited nutrient tor for plant growth and why an influx of phosphorus can pro-

duce immediate and dramatic effects.

The element phosphorus (P) is a key component of cell mem-

branes and of several molecules vital for life, including DNA, Food webs Aquatic producers take up phosphates from

RNA, ATP, and ADP (pp. 57, 50). Although phosphorus is surrounding waters, whereas terrestrial producers take up

indispensable for life, the amount of phosphorus in organisms phosphorus from soil water through their roots. Primary con-

is dwarfed by the vast amounts in rocks, soil, sediments, and sumers acquire phosphorus from plant tissues and pass it on

the oceans. Unlike the carbon and nitrogen cycles, the phos- to secondary and tertiary consumers (Chapter 4). Consum-

phorus cycle (Figure 5.20) has no appreciable atmospheric ers also pass phosphorus to the soil through the excretion of

component besides the transport of tiny amounts in wind- waste. Decomposers break down phosphorus-rich organisms

blown dust and sea spray. and their wastes and, in so doing, return phosphorus to the soil.

Geology and phosphorus availability The vast We affect the phosphorus cycle

majority of Earth’s phosphorus is contained within rocks

and is released only by weathering (p. 237), which releases People increase phosphorus concentrations in surface waters

phosphate ions (PO ) into water. Phosphates dissolved in through runoff of the phosphorus-rich fertilizers we apply to

3−

4

lakes or in the oceans precipitate into solid form, settle to the lawns and farmlands. A 2008 study determined that an aver-

bottom, and reenter the lithosphere’s phosphorus reservoir age hectare of land in the Chesapeake Bay region received a

Biotic cycling

Biotic cycling

1150

1150

Atmosphere

Consumers Producers Transport of dust and seaspray 1

Transport of dust and seaspray 1

Decomposers

Uptake 2 Mineable rock

Uptake 2

12,800

Weathering

Weathering

Mining 25

Mining 25

Rivers

Runoff Erosion Land plants

Runoff

Erosion

21 500 Consumers

21

Pollution CHAPTER 5 • Envi R onm E n TA l S y STE m S A nd E C o S y STE m E C ology

Pollution

Fertilizers

Uptake

and detergents GeologicGeologic Uptake

85

Burial uplift 85

Burial

uplift

19

19 Decomposers

Oceans

Burial 2

90,000 Burial 2 Soils

66,000

Sediment and sedimentary rock

4,000,000,000

Figure 5.20 The phosphorus cycle summarizes the many routes that phosphorus atoms take as they

move through the environment. Gray arrows represent fluxes among reservoirs, or pools, for phosphorus.

Most phosphorus resides underground in rock and sediment. Rocks containing phosphorus are uplifted geolog-

ically and slowly weathered away. Small amounts of phosphorus cycle through food webs, where this nutrient is

often a limiting factor for plant growth. In the figure, pool names are printed in black type, and numbers in black

type represent pool sizes expressed in teragrams (units of 10 g) of phosphorus. Processes, printed in italic red

12

type, give rise to fluxes, printed in italic red type and expressed in teragrams of phosphorus per year. Data from

Schlesinger, W.H., 2013. Biogeochemistry: An analysis of global change, 3rd ed. Academic Press, London. 145

M05_WITH7428_05_SE_C05.indd 145 12/12/14 2:56 PM