Page 566 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 566

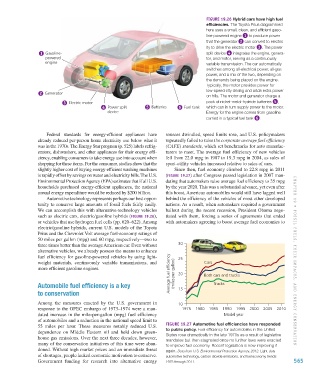

FIGURE 19.26 Hybrid cars have high fuel

efficiencies. The Toyota Prius diagrammed

here uses a small, clean, and efficient gaso-

line-powered engine 1 to produce power

that the generator 2 can convert to electric-

ity to drive the electric motor 3 . The power

1 Gasoline- split device 4 integrates the engine, genera-

powered tor, and motor, serving as a continuously

engine variable transmission. The car automatically

switches among all-electrical power, all-gas

power, and a mix of the two, depending on

the demands being placed on the engine.

Typically, the motor provides power for

low-speed city driving and adds extra power

2 Generator

on hills. The motor and generator charge a

3 Electric motor pack of nickel-metal-hydride batteries 5 ,

4 Power split 5 Batteries 6 Fuel tank which can in turn supply power to the motor.

device Energy for the engine comes from gasoline

carried in a typical fuel tank 6 .

Federal standards for energy-efficient appliances have sources dwindled, speed limits rose, and U.S. policymakers

already reduced per-person home electricity use below what it repeatedly failed to raise the corporate average fuel efficiency

was in the 1970s. The Energy Star program (p. 525) labels refrig- (CAFE) standards, which set benchmarks for auto manufac-

erators, dishwashers, and other appliances for their energy effi- turers to meet. The average fuel efficiency of new vehicles

ciency, enabling consumers to take energy use into account when fell from 22.0 mpg in 1987 to 19.3 mpg in 2004, as sales of

shopping for these items. For the consumer, studies show that the sport-utility vehicles increased relative to sales of cars.

slightly higher cost of buying energy-efficient washing machines Since then, fuel economy climbed to 22.8 mpg in 2011

is rapidly offset by savings on water and electricity bills. The U.S. (FIGURE 19.27) after Congress passed legislation in 2007 man-

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that if all U.S. dating that automakers raise average fuel efficiency to 35 mpg

households purchased energy-efficient appliances, the national by the year 2020. This was a substantial advance, yet even after

annual energy expenditure would be reduced by $200 billion. this boost, American automobiles would still have lagged well

Automotive technology represents perhaps our best oppor- behind the efficiency of the vehicles of most other developed

tunity to conserve large amounts of fossil fuels fairly easily. nations. As a result, when automakers required a government

We can accomplish this with alternative-technology vehicles bailout during the recent recession, President Obama nego-

such as electric cars, electric/gasoline hybrids (FIGURE 19.26), tiated with them, forcing a series of agreements that ended

or vehicles that use hydrogen fuel cells (pp. 620–622). Among with automakers agreeing to boost average fuel economies to

electric/gasoline hybrids, current U.S. models of the Toyota

Prius and the Chevrolet Volt average fuel-economy ratings of

50 miles per gallon (mpg) and 60 mpg, respectively—two to

three times better than the average American car. Even without 30

alternative vehicles, we already possess the means to enhance

fuel efficiency for gasoline-powered vehicles by using light- 25

weight materials, continuously variable transmissions, and Cars CHAPTER 19 • FOSSIL FUELS, THEIR IMPA CT S, AND ENERGY CONSERVATI ON

more efficient gasoline engines. Average fuel efficiency (miles per gallon) 20 Both cars and trucks

Automobile fuel efficiency is a key 15 Trucks

to conservation

Among the measures enacted by the U.S. government in 10

response to the OPEC embargo of 1973–1974 were a man- 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

dated increase in the mile-per-gallon (mpg) fuel efficiency Model year

of automobiles and a reduction in the national speed limit to

55 miles per hour. These measures notably reduced U.S. FIGURE 19.27 Automotive fuel efficiencies have responded

dependence on Middle Eastern oil and held down green- to public policy. Fuel efficiency for automobiles in the United

States rose dramatically in the late 1970s as a result of legislative

house gas emissions. Over the next three decades, however, mandates but then stagnated once no further laws were enacted

many of the conservation initiatives of this time were aban- to improve fuel economy. Recent legislation is now improving it

doned. Without high market prices and an immediate threat again. Data from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2012. Light-duty

of shortages, people lacked economic motivation to conserve. automotive technology, carbon dioxide emissions, and fuel economy trends:

Government funding for research into alternative energy 1975 through 2011. 565

M19_WITH7428_05_SE_C19.indd 565 12/12/14 5:23 PM