Page 8 - The Empowered Nurse - Spring

P. 8

empower_spring2020.qxp_Layout 1 6/23/20 11:52 AM Page 8

06

THE EMPOWERED NURSE

2

THE VISION

This recurring column focuses on searching and critiquing the literature,

teaching the skills required to “see” relevant findings and synthesizing the evidence.

Knowledge as a keystone to practice

According to the Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary, a

keystone is (alternatively) defined as “the central principle or

part of a policy, system, etc., on which all else depends” (“Key-

stone,” 2020). Friedman proposed the notion of knowledge as a

keystone in current and future clinical practice (figure 1). The

cyclical nature of the model further illustrates the vital role

knowledge plays in learning health systems and quality improve-

ment initiatives. Information professionals, clinical champions,

and evidence-based practice scholars have long known this, yet it

is refreshing to see further validation.

However, there is no time to celebrate. It is well known

there is a substantial lag time for research to translate from

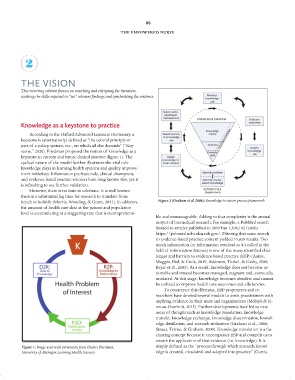

bench to bedside (Morris, Wooding, & Grant, 2011). In addition, Figure 2 (Graham et al 2006): Knowledge-to-action process framework

the amount of health care data at the patient and population

level is accumulating at a staggering rate that is incomprehensi-

ble and unmanageable. Adding to that complexity is the annual

output of biomedical research. For example, a PubMed search

limited to articles published in 2019 has 1,398,182 results

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. Filtering that same search

to evidence-based practice content yielded 55,629 results. Too

much information (or information overload as it’s called in the

field of Information Science) is one of the many identified chal-

lenges and barriers to evidence-based practice (EBP) (Aakre,

Maggio, Fiol, & Cook, 2019; Atkinson, Turkel, & Cashy, 2008;

Bryar et al., 2003). As a result, knowledge does not become ac-

tionable and instead becomes managed, stagnant and, eventually,

outdated. At this stage, knowledge becomes obsolete and cannot

be utilized to improve health care outcomes and efficiencies.

To counteract this dilemma, EBP proponents and re-

searchers have devised several models to assist practitioners with

applying evidence in their units and organizations (Melnyk & Fi-

neout-Overholt, 2015). Further developments have led to new

areas of thought such as knowledge translation, knowledge

transfer, knowledge exchange, knowledge dissemination, knowl-

edge distillation, and research utilization (Graham et al., 2006;

Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2009). Knowledge translation is a fas-

cinating concept because it encompasses EBP and compels us to

ensure the application of that evidence (i.e. knowledge). It is

Figure 1: Image used with permission from Charles Friedman, simply defined as the “process through which research knowl-

University of Michigan Learning Health Sciences edge is created, circulated, and adopted into practice” (Curtis,