Page 212 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 212

ARAMAEANS AND PHOENICIANS IN SYRIA

water-gate81 to which we have referred already (p. 165). It depicts a libation ceremony

also represented at Malatya (Plate 133B). The ritual and the attributes of the god cvi-

dcntly survived, but the rendering shows a translation of the old theme into the north

Syrian idiom of the eighth century. Its companion piece,82 also from the water-gate,

shows that the king wore a beard, and he is seen at table, attended by a servant with a

fly-wliisk and by a lute-player, in accordance with the Assyrianizing fashions of the time.

The lute, widi its cord and tassels tied to the neck, resembles one depicted at Zin^irli, but

not the Hittitc instrument.83

There are, however, some reliefs at Carchcmish representing named kings of the ninth

and eighth centuries b.c. They are less summarily executed.84 A stela found at Til Barsip,

showing a weather-god under a winged disk, seems also to belong to the ninth century B.c.85

The later reliefs at Carchcmish draw heavily on the Mesopotamian repertoire; there is,

again at the water-gate, a winged lion with the claws of a bird of prey and a fantastic

is

ii

fa

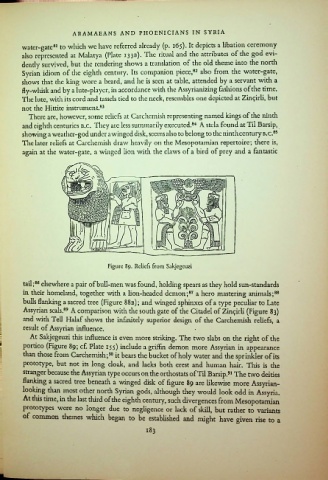

Figure S9. Reliefs from Sakjegcuzi

tail;86 elsewhere a pair of bull-men was found, holding spears as they hold sun-standards

in their homeland, together with a lion-headed demon;87 a hero mastering animals; 88

bulls flanking a sacred tree (Figure 88 b) ; and winged sphinxes of a type peculiar to Late

Assyrian seals.89 A comparison with die south gate of the Citadel of Zin^irh (Figure 83)

and with Tell Halaf shows the infinitely superior design of the Carchemish reliefs, a

result of Assyrian influence.

At Sakjegeuzi this influence is even more striking. The two slabs on the right of the

portico (Figure 89; cf. Plate 155) include a griffin demon more Assyrian in appearance

than those from Carchemish;90 it bears the bucket of holy water and the sprinkler of its

prototype, but not its long cloak, and lacks both crest and human hair. This is the

stranger because the Assyrian type occurs on the orthostats of Til Barsip.91 The two deities

flanking a sacred tree beneath a winged disk of figure 89 are likewise more Assyrian-

looking than most other north Syrian gods, although they would look odd in Assyria.

At tills time, in the last third of the eighth century, such divergences from Mesopotamian

prototypes were no longer due to negligence or lack of skill, but radier to variants

of common themes which began to be established and might have given rise to a

183

I