Page 20 - BiTS_10_OCTOBER_2024_Neat

P. 20

This was around 1953, and it was a turning point in his life, as thoughts of returning south to

life as a farmer were overtaken by the possibilities of being a bluesman.

He bought himself a Kay guitar and a small amplifier and spent hours practising in front of the

open apartment window. He must have improved very quickly, because the neighbours were

apparently happy to listen to him, and one day the owner of the local Club Alibi knocked on his

door - he had been let down by a band that night, and wondered whether Otis would stand in.

“The man said, I’ll pay you five dollars. Five dollars for me playing my guitar!? I thought that

was terrific!” The audience seemed to like it as well, and he soon ended up working three or

four nights a week, which eventually meant he was forced to quit his day job.

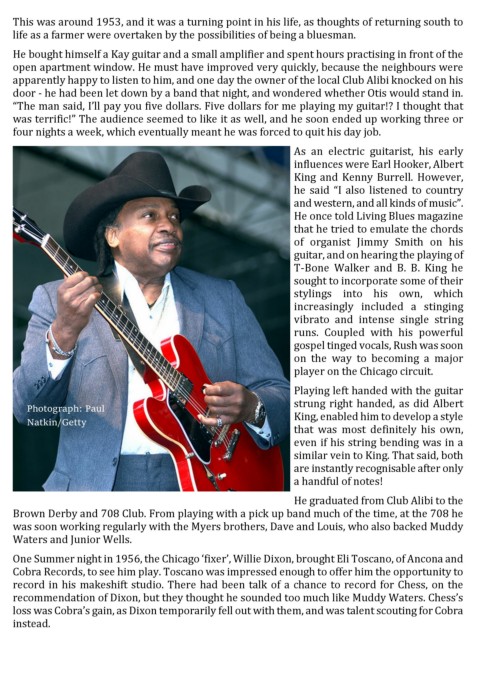

As an electric guitarist, his early

influences were Earl Hooker, Albert

King and Kenny Burrell. However,

he said “I also listened to country

and western, and all kinds of music”.

He once told Living Blues magazine

that he tried to emulate the chords

of organist Jimmy Smith on his

guitar, and on hearing the playing of

T-Bone Walker and B. B. King he

sought to incorporate some of their

stylings into his own, which

increasingly included a stinging

vibrato and intense single string

runs. Coupled with his powerful

gospel tinged vocals, Rush was soon

on the way to becoming a major

player on the Chicago circuit.

Playing left handed with the guitar

strung right handed, as did Albert

Photograph: Paul

King, enabled him to develop a style

Natkin/Getty

that was most definitely his own,

Images

even if his string bending was in a

similar vein to King. That said, both

are instantly recognisable after only

a handful of notes!

He graduated from Club Alibi to the

Brown Derby and 708 Club. From playing with a pick up band much of the time, at the 708 he

was soon working regularly with the Myers brothers, Dave and Louis, who also backed Muddy

Waters and Junior Wells.

One Summer night in 1956, the Chicago ‘fixer’, Willie Dixon, brought Eli Toscano, of Ancona and

Cobra Records, to see him play. Toscano was impressed enough to offer him the opportunity to

record in his makeshift studio. There had been talk of a chance to record for Chess, on the

recommendation of Dixon, but they thought he sounded too much like Muddy Waters. Chess’s

loss was Cobra’s gain, as Dixon temporarily fell out with them, and was talent scouting for Cobra

instead.