Page 436 - Krugmans Economics for AP Text Book_Neat

P. 436

worldwide economic growth. The biggest of these issues involves the impact of fossil-

fuel consumption on the world’s climate.

Burning coal and oil releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. There is broad sci-

entific consensus that rising levels of carbon dioxide and other gases are causing a

greenhouse effect on the Earth, trapping more of the sun’s energy and raising the

planet’s overall temperature. And rising temperatures may impose high human and

economic costs: rising sea levels may flood coastal areas; changing climate may disrupt

agriculture, especially in poor countries; and so on.

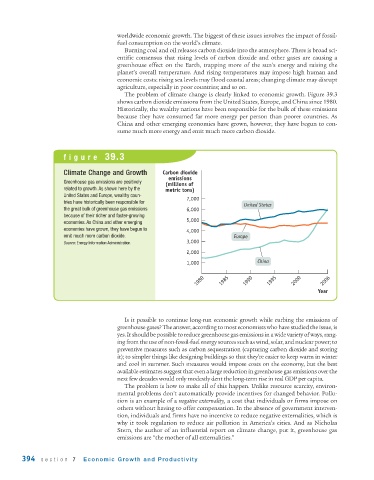

The problem of climate change is clearly linked to economic growth. Figure 39.3

shows carbon dioxide emissions from the United States, Europe, and China since 1980.

Historically, the wealthy nations have been responsible for the bulk of these emissions

because they have consumed far more energy per person than poorer countries. As

China and other emerging economies have grown, however, they have begun to con-

sume much more energy and emit much more carbon dioxide.

figure 39.3

Climate Change and Growth Carbon dioxide

emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions are positively

(millions of

related to growth. As shown here by the metric tons)

United States and Europe, wealthy coun- 7,000

tries have historically been responsible for United States

the great bulk of greenhouse gas emissions 6,000

because of their richer and faster-growing

economies. As China and other emerging 5,000

economies have grown, they have begun to 4,000

emit much more carbon dioxide. Europe

3,000

Source: Energy Information Administration.

2,000

1,000 China

1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2006

Year

Is it possible to continue long - run economic growth while curbing the emissions of

greenhouse gases? The answer, according to most economists who have studied the issue, is

yes. It should be possible to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in a wide variety of ways, rang-

ing from the use of non -fossil -fuel energy sources such as wind, solar, and nuclear power; to

preventive measures such as carbon sequestration (capturing carbon dioxide and storing

it); to simpler things like designing buildings so that they’re easier to keep warm in winter

and cool in summer. Such measures would impose costs on the economy, but the best

available estimates suggest that even a large reduction in greenhouse gas emissions over the

next few decades would only modestly dent the long-term rise in real GDP per capita.

The problem is how to make all of this happen. Unlike resource scarcity, environ-

mental problems don’t automatically provide incentives for changed behavior. Pollu-

tion is an example of a negative externality, a cost that individuals or firms impose on

others without having to offer compensation. In the absence of government interven-

tion, individuals and firms have no incentive to reduce negative externalities, which is

why it took regulation to reduce air pollution in America’s cities. And as Nicholas

Stern, the author of an influential report on climate change, put it, greenhouse gas

emissions are “the mother of all externalities.”

394 section 7 Economic Growth and Productivity