Page 724 - Krugmans Economics for AP Text Book_Neat

P. 724

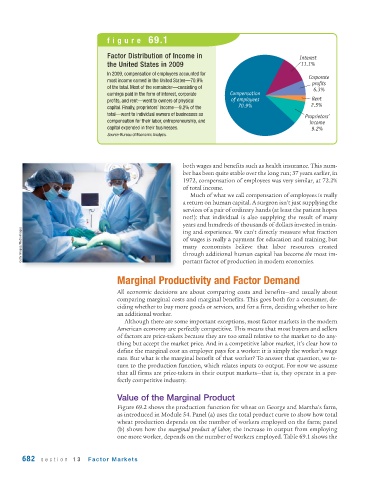

figure 69.1

Factor Distribution of Income in Interest

the United States in 2009 11.1%

In 2009, compensation of employees accounted for

Corporate

most income earned in the United States—70.9%

profits

of the total. Most of the remainder—consisting of 6.3%

earnings paid in the form of interest, corporate Compensation

profits, and rent—went to owners of physical of employees Rent

capital. Finally, proprietors’ income—9.2% of the 70.9% 2.5%

total—went to individual owners of businesses as

Proprietors’

compensation for their labor, entrepreneurship, and income

capital expended in their businesses. 9.2%

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

both wages and benefits such as health insurance. This num-

ber has been quite stable over the long run; 37 years earlier, in

1972, compensation of employees was very similar, at 72.2%

of total income.

Much of what we call compensation of employees is really

a return on human capital. A surgeon isn’t just supplying the

services of a pair of ordinary hands (at least the patient hopes

not!): that individual is also supplying the result of many

years and hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in train-

Getty Images/MedioImages of wages is really a payment for education and training, but

ing and experience. We can’t directly measure what fraction

many economists believe that labor resources created

through additional human capital has become the most im-

portant factor of production in modern economies.

Marginal Productivity and Factor Demand

All economic decisions are about comparing costs and benefits—and usually about

comparing marginal costs and marginal benefits. This goes both for a consumer, de-

ciding whether to buy more goods or services, and for a firm, deciding whether to hire

an additional worker.

Although there are some important exceptions, most factor markets in the modern

American economy are perfectly competitive. This means that most buyers and sellers

of factors are price-takers because they are too small relative to the market to do any-

thing but accept the market price. And in a competitive labor market, it’s clear how to

define the marginal cost an employer pays for a worker: it is simply the worker’s wage

rate. But what is the marginal benefit of that worker? To answer that question, we re-

turn to the production function, which relates inputs to output. For now we assume

that all firms are price-takers in their output markets—that is, they operate in a per-

fectly competitive industry.

Value of the Marginal Product

Figure 69.2 shows the production function for wheat on George and Martha’s farm,

as introduced in Module 54. Panel (a) uses the total product curve to show how total

wheat production depends on the number of workers employed on the farm; panel

(b) shows how the marginal product of labor, the increase in output from employing

one more worker, depends on the number of workers employed. Table 69.1 shows the

682 section 13 Factor Markets