Page 165 - Ming_China_Courts_and_Contacts_1400_1450 Craig lunas

P. 165

changjuan tu 普渡明太袓長卷圖) in the Tibet Museum. It

recordsthe miraculous occurrences during memorial

services performed by the Fifth Karmapa in 1407 at

Nanjing’s largest imperially sponsored temple, Linggusi

靈谷寺 (Numinous Valley Monastery), for the Hongwu

emperor and Empress Ma, along with Hongwu’s parents, in

19

a series of 49 narrative scenes (see Pl. 14.4a–c). On one

level this painting can be viewed as containing an ulterior

motive, as rumours circulated of Yongle’s possible Mongol or

Korean ancestry after he seized the throne from his nephew

with assistance from Mongol cavalry in 1402. Questioning

Yongle’s ethnicity – denying his very Chinese identity – has

also been a typical means by which to isolate and

marginalise his interests in Tibetan Buddhism. The

20

manner in which Yongle came to power naturally put a

cloud over his reign and made him concerned about the

image of his own legitimacy. The handscroll had a clear

political agenda in confirming the legitimacy of Yongle’s

reign, and made use of similar strategies that the Mongol

court employed to project power across Asia, such as the

multilingual inscriptions found on this handscroll, as also

seen on Yuan public works such as the aforementioned

Juyong Pass.

Beyond such well-publicised projects is the 1413 missive

scroll which the Yongle emperor sent to the Fifth Karmapa

describing the famous eunuch admiral Zheng He’s 鄭和

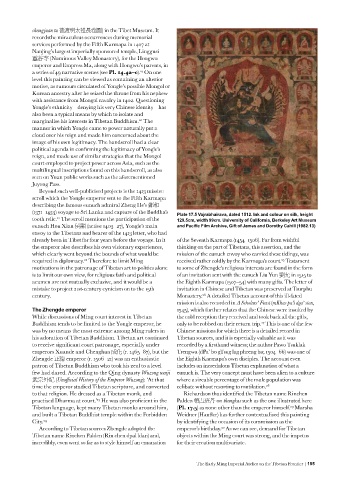

(1371–1433) voyage to Sri Lanka and capture of the Buddha’s Plate 17.5 Vajrabhairava, dated 1512. Ink and colour on silk, height

21

tooth relic. The scroll mentions the participation of the 129.5cm, width 99cm. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum

eunuch Hou Xian 侯顯 (active 1403–27), Yongle’s main and Pacific Film Archive, Gift of James and Dorothy Cahill (1982.13)

envoy to the Tibetans and bearer of the 1413 letter, who had

already been in Tibet for four years before the voyage. In it of the Seventh Karmapa (1454–1506). Far from wishful

the emperor also describes his own visionary experiences, thinking on the part of Tibetans, this assertion, and the

which clearly went beyond the bounds of what would be mission of the eunuch envoy who carried these tidings, was

required in diplomacy. Therefore to limit Ming received rather coldly by the Karmapa’s court. Testament

22

25

motivations in the patronage of Tibetan art to politics alone to some of Zhengde’s religious interests are found in the form

is to limit our own view, for religious faith and political of an invitation sent with the eunuch Liu Yun 劉允 in 1515 to

acumen are not mutually exclusive, and it would be a the Eighth Karmapa (1507–54) with many gifts. The letter of

mistake to project 21st-century cynicism on to the 15th invitation in Chinese and Tibetan was preserved at Tsurphu

century. Monastery. A detailed Tibetan account of this ill-fated

26

mission is also recorded in A Scholars’ Feast (mKhas pa’i dga’ ston,

The Zhengde emperor 1545), which further relates that the Chinese were insulted by

While discussions of Ming court interest in Tibetan the cold reception they received and took back all the gifts,

Buddhism tends to be limited to the Yongle emperor, he only to be robbed on their return trip. This is one of the few

27

was by no means the most extreme among Ming rulers in Chinese missions for which there is a detailed record in

his adoration of Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan art continued Tibetan sources, and it is especially valuable as it was

to receive significant court patronage, especially under recorded by a firsthand witness; the author Pawo Tsuklak

emperors Xuande and Chenghua 成化 (r. 1465–87), but the Trengwa (dPa’ bo gTsug lag phreng ba; 1504–66) was one of

Zhengde 正德 emperor (r. 1506–21) was an enthusiastic the Eighth Karmapa’s own disciples. The account even

patron of Tibetan Buddhism who took his zeal to a level includes an incredulous Tibetan explanation of what a

few had dared. According to the Qing dynasty Wuzong waiji eunuch is. The very concept must have been alien to a culture

武宗外紀 (Unofficial History of the Emperor Wuzong): ‘At that where a sizeable percentage of the male population was

time the emperor studied Tibetan scripture, and converted celibate without resorting to mutilation.

28

to that religion. He dressed as a Tibetan monk, and Richardson thus identified the Tibetan name Rinchen

practised Dharma at court.’ He was also proficient in the Palden 領占班丹 on thangkas such as the one illustrated here

23

Tibetan language, kept many Tibetan monks around him, (Pl. 17.5) as none other than the emperor himself. Marsha

29

and built a Tibetan Buddhist temple within the Forbidden Weidner (Haufler) has further contextualised this painting

City. by identifying the occasion of its commission as the

24

According to Tibetan sources Zhengde adopted the emperor’s birthday. As we can see, demand for Tibetan

30

Tibetan name Rinchen Palden (Rin chen dpal ldan) and, objects within the Ming court was strong, and the impetus

incredibly, even went so far as to style himself an emanation for their creation multivariate.

The Early Ming Imperial Atelier on the Tibetan Frontier | 155