Page 163 - Ming_China_Courts_and_Contacts_1400_1450 Craig lunas

P. 163

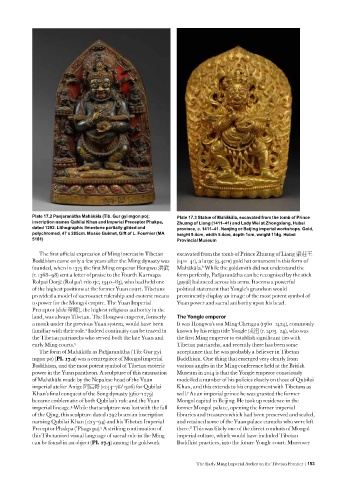

Plate 17.2 Panjaranātha Mahākāla (Tib. Gur gyi mgon po); Plate 17.3 Statue of Mahākāla, excavated from the tomb of Prince

inscription names Qubilai Khan and Imperial Preceptor Phakpa, Zhuang of Liang (1411–41) and Lady Wei at Zhongxiang, Hubei

dated 1292. Lithographic limestone partially gilded and province, c. 1411–41. Nanjing or Beijing imperial workshops. Gold,

polychromed, 47 x 285cm. Musée Guimet, Gift of L. Fournier (MA height 9.4cm, width 5.4cm, depth 1cm, weight 114g. Hubei

5181) Provincial Museum

The first official expression of Ming interest in Tibetan excavated from the tomb of Prince Zhuang of Liang 梁莊王

Buddhism came only a few years after the Ming dynasty was (1411–41), a large (9.4cm) gold hat ornament in this form of

6

founded, when in 1375 the first Ming emperor Hongwu 洪武 Mahākāla. While the goldsmith did not understand the

(r. 1368–98) sent a letter of praise to the Fourth Karmapa form perfectly, Pañjaranātha can be recognised by the stick

Rolpai Dorjé (Rol pa’i rdo rje; 1340–83), who had held one (gaṇḍi) balanced across his arms. It seems a powerful

of the highest positions at the former Yuan court. Tibetans political statement that Yongle’s grandson would

provided a model of sacrosanct rulership and esoteric means prominently display an image of the most potent symbol of

to power for the Mongol empire. The Yuan Imperial Yuan power and sacral authority upon his head.

Preceptor (dishi 帝師), the highest religious authority in the

land, was always Tibetan. The Hongwu emperor, formerly The Yongle emperor

a monk under the previous Yuan system, would have been It was Hongwu’s son Ming Chengzu (1360–1424), commonly

2

familiar with their role. Indeed continuity can be traced in known by his reign title Yongle 成祖 (r. 1403–24), who was

the Tibetan patriarchs who served both the late Yuan and the first Ming emperor to establish significant ties with

early Ming courts. 3 Tibetan patriarchs, and recently there has been some

The form of Mahākāla as Pañjaranātha (Tib: Gur gyi acceptance that he was probably a believer in Tibetan

mgon po) (Pl. 17.2) was a centrepiece of Mongol imperial Buddhism. One thing that emerged very clearly from

Buddhism, and the most potent symbol of Tibetan esoteric various angles in the Ming conference held at the British

power in the Yuan pantheon. A sculpture of this emanation Museum in 2014 is that the Yongle emperor consciously

of Mahākāla made by the Nepalese head of the Yuan modelled a number of his policies closely on those of Qubilai

imperial atelier Anige 阿尼哥 (1244–78/1306) for Qubilai Khan, and this extends to his engagement with Tibetans as

Khan’s final conquest of the Song dynasty (960–1279) well. As an imperial prince he was granted the former

7

became emblematic of both Qubilai’s rule and the Yuan Mongol capital in Beijing. He took up residence in the

imperial lineage. While that sculpture was lost with the fall former Mongol palace, opening the former imperial

4

of the Qing, this sculpture dated 1292 bears an inscription libraries and treasures which had been preserved and sealed,

naming Qubilai Khan (1215–94) and his Tibetan Imperial and retained some of the Yuan palace eunuchs who were left

Preceptor Phakpa (’Phags pa). A striking continuation of there. This was likely one of the direct conduits of Mongol

8

5

this Tibetanised visual language of sacral rule in the Ming imperial culture, which would have included Tibetan

can be found in an object (Pl. 17.3) among the goldwork Buddhist practices, into the future Yongle court. Moreover

The Early Ming Imperial Atelier on the Tibetan Frontier | 153