Page 71 - Christie's London Fine Chinese Ceramics Nov. 2019

P. 71

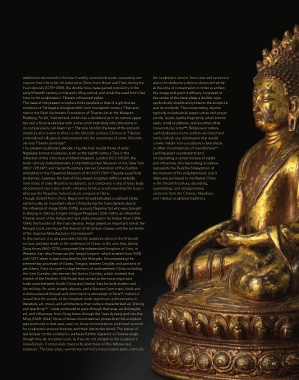

additional row encircles the base’s subtly constricted waist, separating one the sculpture’s interior from view and secures in

register from the other. Introduced to China from Nepal and Tibet during the place the dedicatory objects deposited within

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368), the double-lotus base gained popularity in the at the time of consecration in order to enliven

early ffteenth century, in the early Ming period, and would be used from that the image and grant it eficacy. Engraved at

time on for sculptures in Tibetan-infuenced styles. the center of the base plate, a double-vajra

The base of the present sculpture fnds parallels in that of a gilt bronze symbolically shields and protects the sculpture

sculpture of Tathagata Amoghasiddhi from fourteenth-century Tibet and and its contents. The consecratory objects

now in the Berti Aschmann Foundation of Tibetan Art at the Museum typically include small paper sutras and prayer

Rietberg, Zurich, Switzerland, which has a double lotus in its narrow upper scrolls, beads, textile fragments, small bronze

tier and a foral arabesque with a vine scroll encircling lotus blossoms in seals, small sculptures, and assorted other

x

its comparatively tall lower tier . The vine scroll in the base of the present consecratory items xviii . Religious in nature,

sculpture also is akin to those in the ffteenth-century, Chinese or Tibetan, such dedicatory items seldom are dated and

embroidered silk panels incorporated into the mountings of some ffteenth- rarely include any information that would

xi

century Tibetan paintings . convey insight into a sculpture’s date, place,

The present sculpture’s slender, ring-like halo recalls those of early or other circumstances of manufacture .

xix

Nepalese bronze sculptures, such as the eighth-century Tara in the Lacking exact counterparts and

xii

collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (IS.9-1989) , the incorporating a varied mixture of styles

tenth-century Avalokiteshvara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and infuences, this fascinating sculpture

(1982.220.14) , and the tenth-century Vak (an Emanation of the Buddha represents the Buddha Shakyamuni at

xiii

xiv

Amitabha) in the Cleveland Museum of Art (1971.170) . Despite superfcial the moment of his enlightenment, and it

similarities, however, the halo of the present sculpture difers markedly likely was produced in northwest China

from those of early Nepalese sculptures, as it comprises a ring of lotus buds in the ffteenth century, absorbing,

incorporated into a vine scroll—echoing the lotus scroll encircling the base— assimilating, and amalgamating

whereas the Nepalese haloes feature tongues of fame. elements from the Chinese, Nepalese,

Though distant from China, Nepal and its sophisticated sculptural styles and Tibetan sculptural traditions.

came to play an important role in China during the Yuan dynasty due to

the infuence of Anige (1245–1306), a young Nepali artist who was brought

to Beijing in 1262 by Drogön Chögyal Phags’pa (1235–1280), an infuential

Tibetan monk of the Sakya sect and state preceptor for Kublai Khan (1215–

1294), the founder of the Yuan dynasty. Anige played an important role at the

Mongol court, serving as the director of all artisan classes and the controller

of the Imperial Manufactories Commission .

xv

In this context, it is very possible that the sculpture dates to the ffteenth

century and was made in the northwest of China, in the area that, during

Song times (960–1279), comprised the independent kingdom of Xixia, or

Western Xia—also known as the Tangut Empire—which existed from 1038

until 1227, when it was conquered by the Mongols. Encompassing the

present-day provinces of Gansu, Ningxia, eastern Qinghai, and portions of

yet others, Xixia occupied a large territory of northwestern China, including

the Hexi Corridor, also termed the Gansu Corridor, which claimed that

stretch of the Northern Silk Route that served as the most important

trade route between North China and Central Asia for both traders and

the military. As such, people, objects, and infuences from many lands and

xvi

cultures passed through and intermixed to advantage in Xixia ; indeed, it

is said that the people of the kingdom made signifcant achievements in

literature, art, music, and architecture, their culture characterized as “shining

and sparkling .” Trade continued to pass through that area, as did people,

xvii

art, and infuences, from Song times through the Yuan dynasty and into the

Ming (1368–1644). None of those circumstances proves that this sculpture

was produced in that area; even so, those circumstances could well account

for sculpture’s unusual features and their distinctive blend. The traces of

red lacquer on the sculpture’s surfaces further argue for a Chinese origin,

though they do not prove such, as they are not integral to the sculpture’s

manufacture. A metal plate covers the open base of this hollow-cast

sculpture. The base plate, sometimes termed a consecratory plate, conceals

69