Page 23 - Chinese Export Porcelain Art, MET MUSEUM 2003

P. 23

imperial workshops between 1716 and

1729 has been well documented. European

enamels on copper-the base material was

covered by an opaque white, painted and

fired in colors that included shades of pink-

were the stimulus, acquired from the Jesuits

as gifts for the Kangxi emperor, who in

turn enlisted several missionaries to teach

the technique. As the materials and firing

methods were applicable to enameling on

metal as well as on porcelain, the famille

rose developed in both media contempo-

raneously, at the end of the Kangxi period;

its earliest datable appearance in export

porcelain is in a service of about 1722 for a

wealthy English merchant, Sir John Lambert

(d. 1723). A difference between the Chinese

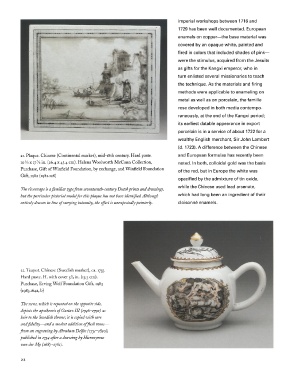

21. Plaque. Chinese (Continental market), mid-i8th century. Hard paste. and European formulas has recently been

x i77/8 in. (26.4 x

Io3/8 45.4 cm). Helena Woolworth McCann Collection, noted. In both, colloidal gold was the basis

Purchase, Gift of Winfield Foundation, by exchange, and Winfield Foundation of the red, but in Europe the white was

Gift, 1982 (I982.128)

opacified by the admixture of tin oxide,

while the Chinese used lead arsenate,

Dutch

is

The riverscape afamiliar typefrom seventeenth-century prints and drawings,

but the particularpictorial modelfor this plaque has not been identified. Although which had long been an ingredient of their

entirely drawn in line of varying intensity, the efect is unexpectedlypainterly. cloisonne enamels.

22. Teapot. Chinese (Swedish market), ca. 1755.

Hard paste. H. with cover 5/4 in. (3.3 cm).

Purchase, Erving Wolf Foundation Gift, 1983

(I983.164a, b)

The scene, which is repeated

on the opposite side,

depicts the apotheosis of Gustav III (1746-1792) as i h

heir to the Swedish throne; it is copied with care

.

andfidelity-and a modest addition of flesh tones- xi.lliE

an

from engraving by Abraham Delfos (1731-1820),

a

in

published I754 after drawing by Hieronymus

van der

My (I687-176I).

22