Page 8 - The Great 401k Rip-Off

P. 8

When discussing the tax impact of 401(k)s, IRAs, and other tax‐deferred plans, we often refer to

taxing the seed (annual deposits) vs. taxing the harvest (retirement income, once you start

withdrawing). If indeed, the tax rate when you spend (harvest) is less than or equal to that when you

are saving (seed), the two are equal. In that case, it makes no difference if you tax the seed or the

harvest, unless it affects your overall tax bracket and Social Security calculations, as reflected above.

On the other hand, if tax rates are higher when you have retired, it can cause a form of double

jeopardy, causing taxes on the harvest to outpace taxes saved on the seed, as well as having a

deleterious effect on your Social Security benefits. If, in addition, you have a pension (actually,

whether you have a pension or not), it can cause additional harm by raising your overall tax rate on

all of your income.

To put this in perspective, if you were to have $50,000 in Social Security income between you and

your spouse, and the income from your tax deferred retirement accounts totaled $50,000 per year,

the total taxes paid would be around $8,100, as your retirement accounts would be 100% taxed in

retirement. However, by converting the retirement funds to accounts that are not taxed in

retirement, income taxes would be zero. That means, over a 20‐year retirement, the difference

between taxing the seed and harvest, even when tax rates remain the same, would be $162,000,

because of the difference in Social Security taxes and difference in tax brackets.

Therefore, tax treatment of these accounts can have a significant impact on the amount of money

you will have to spend during retirement. However, the primary threats to holders of these plans is

the impact of fees and market losses.

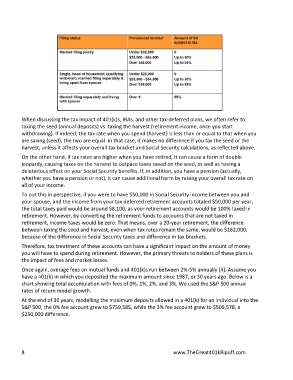

Once again, average fees on mutual funds and 401(k)s run between 2%‐5% annually [4]. Assume you

have a 401(k) in which you deposited the maximum amount since 1987, or 30 years ago. Below is a

chart showing total accumulation with fees of 0%, 1%, 2%, and 3%. We used the S&P 500 annual

rates of return model growth.

At the end of 30 years, modelling the maximum deposits allowed in a 401(k) for an individual into the

S&P 500, the 0% fee account grew to $759,585, while the 3% fee account grew to $509,578, a

$250,000 difference.

8 www.TheGreat401kRipoff.com