Page 55 - Financial Statement Analysis

P. 55

sub79433_ch01.qxd 4/7/08 11:20 AM Page 32

32 Financial Statement Analysis

To varying degrees, sales impact nearly all expenses, and it is useful to know what per-

centage of sales is represented by each expense item. An exception is income taxes,

which is related to pre-tax income and not sales.

Temporal (time) comparisons of a company’s common-size statements are useful in

revealing any proportionate changes in accounts within groups of assets, liabilities,

expenses, and other categories. Still, we must exercise care in interpreting changes and

trends as shown in Illustration 1.3.

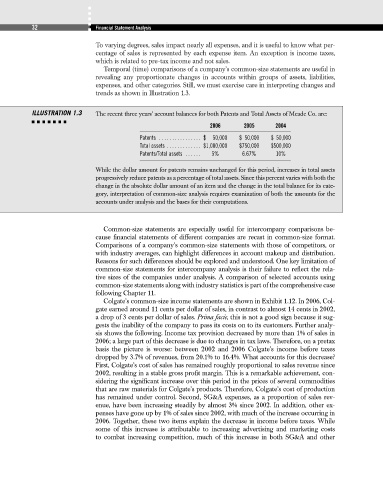

ILLUSTRATION 1.3 The recent three years’ account balances for both Patents and Total Assets of Meade Co. are:

2006 2005 2004

Patents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . $ 50,000 $ 50,000 $ 50,000

Total assets . . . . . . . . . . . . . $1,000,000 $750,000 $500,000

Patents/Total assets . . . . . . 5% 6.67% 10%

While the dollar amount for patents remains unchanged for this period, increases in total assets

progressively reduce patents as a percentage of total assets. Since this percent varies with both the

change in the absolute dollar amount of an item and the change in the total balance for its cate-

gory, interpretation of common-size analysis requires examination of both the amounts for the

accounts under analysis and the bases for their computations.

Common-size statements are especially useful for intercompany comparisons be-

cause financial statements of different companies are recast in common-size format.

Comparisons of a company’s common-size statements with those of competitors, or

with industry averages, can highlight differences in account makeup and distribution.

Reasons for such differences should be explored and understood. One key limitation of

common-size statements for intercompany analysis is their failure to reflect the rela-

tive sizes of the companies under analysis. A comparison of selected accounts using

common-size statements along with industry statistics is part of the comprehensive case

following Chapter 11.

Colgate’s common-size income statements are shown in Exhibit 1.12. In 2006, Col-

gate earned around 11 cents per dollar of sales, in contrast to almost 14 cents in 2002,

a drop of 3 cents per dollar of sales. Prima facie, this is not a good sign because it sug-

gests the inability of the company to pass its costs on to its customers. Further analy-

sis shows the following. Income tax provision decreased by more than 1% of sales in

2006; a large part of this decrease is due to changes in tax laws. Therefore, on a pretax

basis the picture is worse: between 2002 and 2006 Colgate’s income before taxes

dropped by 3.7% of revenues, from 20.1% to 16.4%. What accounts for this decrease?

First, Colgate’s cost of sales has remained roughly proportional to sales revenue since

2002, resulting in a stable gross profit margin. This is a remarkable achievement, con-

sidering the significant increase over this period in the prices of several commodities

that are raw materials for Colgate’s products. Therefore, Colgate’s cost of production

has remained under control. Second, SG&A expenses, as a proportion of sales rev-

enue, have been increasing steadily by almost 3% since 2002. In addition, other ex-

penses have gone up by 1% of sales since 2002, with much of the increase occurring in

2006. Together, these two items explain the decrease in income before taxes. While

some of this increase is attributable to increasing advertising and marketing costs

to combat increasing competition, much of this increase in both SG&A and other