Page 118 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 118

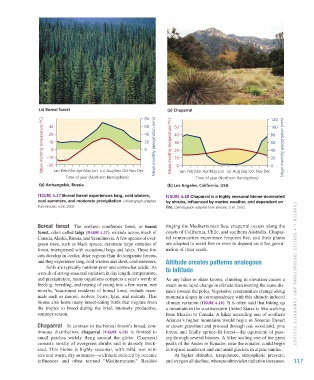

(a) Boreal forest 80 (a) Chaparral 120

Mean monthly temperature (ºC) –10 40 Mean monthly precipitation (mm) Mean monthly temperature (ºC) 40 80 Mean monthly precipitation (mm)

60

30

100

50

20

20

10

60

30

0

0

20

40

10

20

–20

Jan Feb Mar AprMay Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Time of year (Northern Hemisphere) 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 0

Time of year (Northern Hemisphere)

(b) Archangelsk, Russia (b) Los Angeles, California, USA

Figure 4.27 Boreal forest experiences long, cold winters, Figure 4.28 Chaparral is a highly seasonal biome dominated

cool summers, and moderate precipitation. Climatograph adapted by shrubs, influenced by marine weather, and dependent on

from Breckle, S.W., 2002. fire. Climatograph adapted from Breckle, S.W., 2002.

Boreal forest The northern coniferous forest, or boreal ringing the Mediterranean Sea, chaparral occurs along the

forest, often called taiga (Figure 4.27), extends across much of coasts of California, Chile, and southern Australia. Chapar-

Canada, Alaska, Russia, and Scandinavia. A few species of ever- ral communities experience frequent fire, and their plants

green trees, such as black spruce, dominate large stretches of are adapted to resist fire or even to depend on it for germi-

forest, interspersed with occasional bogs and lakes. These for- nation of their seeds.

ests develop in cooler, drier regions than do temperate forests,

and they experience long, cold winters and short, cool summers. Altitude creates patterns analogous

Soils are typically nutrient-poor and somewhat acidic. As to latitude

a result of strong seasonal variation in day length, temperature, CHAPTER 4 • S PEC i ES i n TERA CT i on S A nd Co mmuni T y E C ology

and precipitation, many organisms compress a year’s worth of As any hiker or skier knows, climbing in elevation causes a

feeding, breeding, and rearing of young into a few warm, wet much more rapid change in climate than moving the same dis-

months. Year-round residents of boreal forest include mam- tance toward the poles. Vegetative communities change along

mals such as moose, wolves, bears, lynx, and rodents. This mountain slopes in correspondence with this altitude-induced

biome also hosts many insect-eating birds that migrate from climate variation (Figure 4.29). It is often said that hiking up

the tropics to breed during the brief, intensely productive, a mountain in the southwestern United States is like walking

summer season. from Mexico to Canada. A hiker ascending one of southern

Arizona’s higher mountains would begin in Sonoran Desert

Chaparral In contrast to the boreal forest’s broad, con- or desert grassland and proceed through oak woodland, pine

tinuous distribution, chaparral (Figure 4.28) is limited to forest, and finally spruce–fir forest—the equivalent of pass-

small patches widely flung around the globe. Chaparral ing through several biomes. A hiker scaling one of the great

consists mostly of evergreen shrubs and is densely thick- peaks of the Andes in Ecuador, near the equator, could begin

eted. This biome is highly seasonal, with mild, wet win- in tropical rainforest and end amid glaciers in alpine tundra.

ters and warm, dry summers—a climate induced by oceanic At higher altitudes, temperature, atmospheric pressure,

influences and often termed “Mediterranean.” Besides and oxygen all decline, whereas ultraviolet radiation increases. 117

M04_WITH7428_05_SE_C04.indd 117 12/12/14 2:55 PM