Page 119 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 119

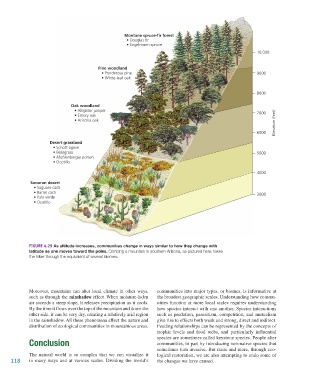

Montane spruce-fir forest

• Douglas fir

• Engelmann spruce

10,000

Pine woodland

• Ponderosa pine 9000

• White-leaf oak

8000

Oak woodland

• Alligator juniper 7000

• Emory oak

• Arizona oak Elevation (feet)

6000

Desert grassland

• Schott agave

• Beargrass 5000

• Muhlenbergia porteri

• Ocotillo

4000

Sonoran desert

• Saguaro cacti

• Barrel cacti 3000

• Palo verde

• Ocotillo

Figure 4.29 As altitude increases, communities change in ways similar to how they change with

latitude as one moves toward the poles. Climbing a mountain in southern Arizona, as pictured here, takes

the hiker through the equivalent of several biomes.

Moreover, mountains can alter local climate in other ways, communities into major types, or biomes, is informative at

such as through the rainshadow effect. When moisture-laden the broadest geographic scales. Understanding how commu-

air ascends a steep slope, it releases precipitation as it cools. nities function at more local scales requires understanding

By the time it flows over the top of the mountain and down the how species interact with one another. Species interactions

other side, it can be very dry, creating a relatively arid region such as predation, parasitism, competition, and mutualism

in the rainshadow. All these phenomena affect the nature and give rise to effects both weak and strong, direct and indirect.

distribution of ecological communities in mountainous areas. Feeding relationships can be represented by the concepts of

trophic levels and food webs, and particularly influential

Conclusion species are sometimes called keystone species. People alter

communities, in part by introducing non-native species that

sometimes turn invasive. But more and more, through eco-

The natural world is so complex that we can visualize it logical restoration, we are also attempting to undo some of

118 in many ways and at various scales. Dividing the world’s the changes we have caused.

M04_WITH7428_05_SE_C04.indd 118 12/12/14 2:55 PM