Page 169 - J. C. Turner - History and Science of Knots

P. 169

A History of Life Support Knots 159

and springy under a shock load. Neither became popular, indeed I have seen

no other reference to them. The knots look complicated to tie. Knotting is

usually of minor interest to climbers; they do not wish to spend much time

learning new knots unless the advantages are substantial and manifest.

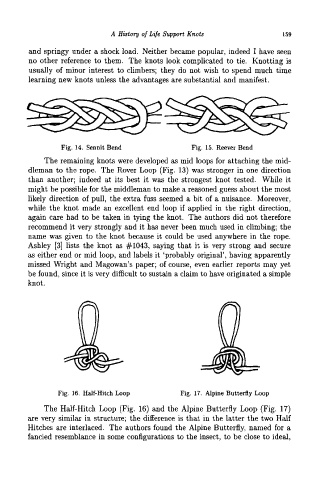

Fig. 14. Sennit Bend Fig. 15. Reever Bend

The remaining knots were developed as mid loops for attaching the mid-

dleman to the rope. The Rover Loop (Fig. 13) was stronger in one direction

than another; indeed at its best it was the strongest knot tested. While it

might be possible for the middleman to make a reasoned guess about the most

likely direction of pull, the extra fuss seemed a bit of a nuisance. Moreover,

while the knot made an excellent end loop if applied in the right direction,

again care had to be taken in tying the knot. The authors did not therefore

recommend it very strongly and it has never been much used in climbing; the

name was given to the knot because it could be used anywhere in the rope.

Ashley [3] lists the knot as #1043, saying that it is very strong and secure

as either end or mid loop, and labels it `probably original', having apparently

missed Wright and Magowan's paper; of course, even earlier reports may yet

be found, since it is very difficult to sustain a claim to have originated a simple

knot.

Fig. 16. Half-Hitch Loop Fig. 17. Alpine Butterfly Loop

The Half-Hitch Loop (Fig. 16) and the Alpine Butterfly Loop (Fig. 17)

are very similar in structure; the difference is that in the latter the two Half

Hitches are interlaced. The authors found the Alpine Butterfly, named for a

fancied resemblance in some configurations to the insect, to be close to ideal,