Page 168 - J. C. Turner - History and Science of Knots

P. 168

158 History and Science of Knots

and criticising many of the knots in common use at that time. They then

developed and named a series of `new knots' (saying `no earlier record has

been traced'), described how to tie them in the practical situations of actual

climbing, and estimated the time needed to tie them and their effects on the

breaking strength of the rope. I know of no other description of the knots used

for climbing that gives so much detail of so many aspects of the knots.

Their paper arose from a dissatisfaction with many of the knots recom-

mended at that time for climbers; many of them could not withstand the

`pulling about by alternate straining and slacking' so commonly found in climb-

ing practice. They were particularly dissatisfied with the Fisherman Loop

(Fig. 4) as a mid loop, though it was the knot most frequently recommended

in manuals . They pointed out that in one direction it was a slip knot, though

optimists ('a term necessarily including all climbers') claimed that no trou-

bles were ever found in practice. The knot also suffered from having the ends

emerging together from the knot in the same direction, rather than in opposite

directions, in line. That meant that under load one end must be subjected to

a very sharp angle, an unsafe procedure. This disadvantage is also shared by

the Overhand Loop (Fig. 1), which was also criticised because it jams, wears

badly and has no spring in it. The authors claim that they developed all the

following knots (Figs. 12,13,14,15,16,17).

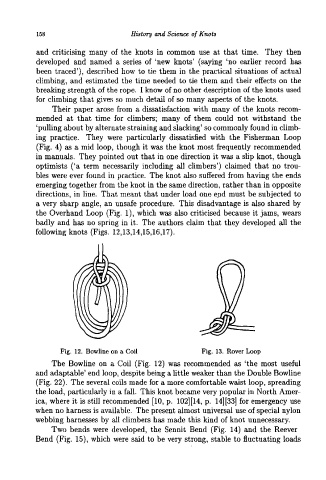

Fig. 12. Bowline on a Coil Fig. 13. Rover Loop

The Bowline on a Coil (Fig. 12) was recommended as `the most useful

and adaptable' end loop, despite being a little weaker than the Double Bowline

(Fig. 22). The several coils made for a more comfortable waist loop, spreading

the load, particularly in a fall. This knot became very popular in North Amer-

ica, where it is still recommended [10, p. 102] [14, p. 14] [33] for emergency use

when no harness is available. The present almost universal use of special nylon

webbing harnesses by all climbers has made this kind of knot unnecessary.

Two bends were developed, the Sennit Bend (Fig. 14) and the Reever

Bend (Fig. 15), which were said to be very strong, stable to fluctuating loads