Page 475 - Bahrain Gov Annual Reports (IV)_Neat

P. 475

67

“The main strata of the Eocene rocks on the island arc seven, namely, from above down

wards :—

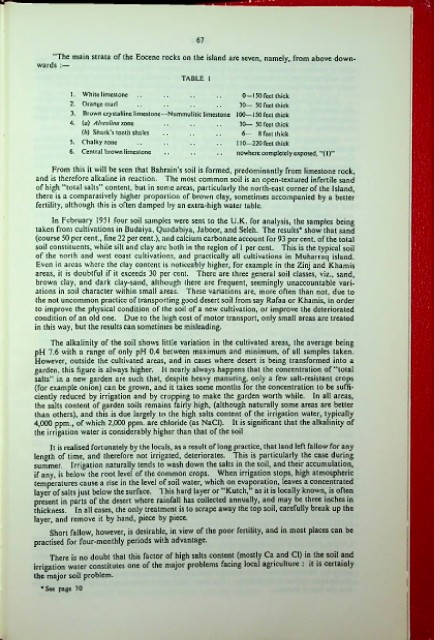

TABLE 1

1. White limestone 0—150 feet thick

2. Orange marl 30— 50 feet thick

3. Brown crystalline limestone—Nummulitic limestone 100—150 feet thick

4. (a) Alveoliita zone 30— 50 feet thick

(b) Shark’s tooth shales 6— 8 feet thick

5. Chalky zone 110—220 feet thick

6. Central brown limestone nowhere completely exposed, “(I)”

From this it will be seen that Bahrain’s soil is formed, predominantly from limestone rock,

and is therefore alkaline in reaction. The most common soil is an open-textured infertile sand

of high “total salts” content, but in some areas, particularly the north-east corner of the Island,

there is a comparatively higher proportion of brown clay, sometimes accompanied by a better

fertility, although this is often damped by an extra-high water table.

In February 1951 four soil samples were sent to the U.K. for analysis, the samples being

taken from cultivations in Budaiya, Quadabiya, Jaboor, and Seleh. The results* show that sand

(course 50 per cent., fine 22 per cent.), and calcium carbonate account for 93 per cent, of the total

soil constituents, while silt and clay are both in the region of 1 per cent. This is the typical soil

of the north and west coast cultivations, and practically all cultivations in Muharraq island.

Even in areas where the clay content is noticeably higher, for example in the Zinj and Khamis

areas, it is doubtful if it exceeds 30 per cent. There are three general soil classes, viz., sand,

brown clay, and dark clay-sand, although there are frequent, seemingly unaccountable vari

ations in soil character within small areas. These variations are, more often than not, due to

the not uncommon practice of transporting good desert soil from say Rafaa or Khamis, in order

to improve the physical condition of the soil of a new cultivation, or improve the deteriorated

condition of an old one. Due to the high cost of motor transport, only small areas arc treated

in this way, but the results can sometimes be misleading.

The alkalinity of the soil shows little variation in the cultivated areas, the average being

pH 7.6 with a range of only pH 0.4 between maximum and minimum, of all samples taken.

However, outside the cultivated areas, and in cases where desert is being transformed into a

garden, this figure is always higher. It nearly always happens that the concentration of “total

salts” in a new garden are such that, despite heavy manuring, only a few salt-resistant crops

(for example onion) can be grown, and it takes some months for the concentration to be suffi

ciently reduced by irrigation and by cropping to make the garden worth while. In all areas,

the salts content of garden soils remains fairly high, (although naturally some areas are belter

than others), and this is due largely to the high salts content of the irrigation water, typically

4,000 ppm., of which 2,000 ppm. arc chloride (as NaCl). It is significant that the alkalinity of

the irrigation water is considerably higher than that of the soil

It is realised fortunately by the locals, as a result of long practice, that land left fallow for any

length of time, and therefore not irrigated, deteriorates. This is particularly the case during

summer. Irrigation naturally tends to wash down the salts in the soil, and their accumulation,

if any, is below the root level of the common crops. When irrigation stops, high atmospheric

temperatures cause a rise in the level of soil water, which on evaporation, leaves a concentrated

layer of salts just below the surface. T his hard layer or “Kutch,” as it is locally known, is often

present in parts of the desert where rainfall has collected annually, and may be three inches in

thickness. In all cases, the only treatment is to scrape away the top soil, carefully break up the

layer, and remove it by hand, piece by piece.

I

Short fallow, however, is desirable, in view of the poor fertility, and in most places can be

practised for four-monthly periods with advantage.

There is no doubt that this factor of high salts content (mostly Ca and Cl) in the soil and

irrigation water constitutes one of the major problems facing local agriculture : it is certainly

the major soil problem.

*See page 70