Page 1188 - Small Animal Internal Medicine, 6th Edition

P. 1188

1160 PART IX Nervous System and Neuromuscular Disorders

VetBooks.ir

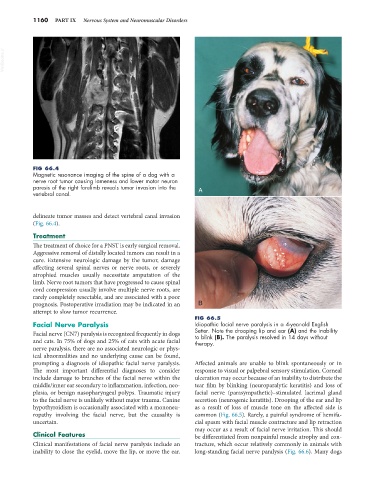

FIG 66.4

Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine of a dog with a

nerve root tumor causing lameness and lower motor neuron

paresis of the right forelimb reveals tumor invasion into the A

vertebral canal.

delineate tumor masses and detect vertebral canal invasion

(Fig. 66.4).

Treatment

The treatment of choice for a PNST is early surgical removal.

Aggressive removal of distally located tumors can result in a

cure. Extensive neurologic damage by the tumor, damage

affecting several spinal nerves or nerve roots, or severely

atrophied muscles usually necessitate amputation of the

limb. Nerve root tumors that have progressed to cause spinal

cord compression usually involve multiple nerve roots, are

rarely completely resectable, and are associated with a poor

prognosis. Postoperative irradiation may be indicated in an B

attempt to slow tumor recurrence.

FIG 66.5

Facial Nerve Paralysis Idiopathic facial nerve paralysis in a 4-year-old English

Facial nerve (CN7) paralysis is recognized frequently in dogs Setter. Note the drooping lip and ear (A) and the inability

to blink (B). The paralysis resolved in 14 days without

and cats. In 75% of dogs and 25% of cats with acute facial therapy.

nerve paralysis, there are no associated neurologic or phys-

ical abnormalities and no underlying cause can be found,

prompting a diagnosis of idiopathic facial nerve paralysis. Affected animals are unable to blink spontaneously or in

The most important differential diagnoses to consider response to visual or palpebral sensory stimulation. Corneal

include damage to branches of the facial nerve within the ulceration may occur because of an inability to distribute the

middle/inner ear secondary to inflammation, infection, neo- tear film by blinking (neuroparalytic keratitis) and loss of

plasia, or benign nasopharyngeal polyps. Traumatic injury facial nerve (parasympathetic)–stimulated lacrimal gland

to the facial nerve is unlikely without major trauma. Canine secretion (neurogenic keratitis). Drooping of the ear and lip

hypothyroidism is occasionally associated with a mononeu- as a result of loss of muscle tone on the affected side is

ropathy involving the facial nerve, but the causality is common (Fig. 66.5). Rarely, a painful syndrome of hemifa-

uncertain. cial spasm with facial muscle contracture and lip retraction

may occur as a result of facial nerve irritation. This should

Clinical Features be differentiated from nonpainful muscle atrophy and con-

Clinical manifestations of facial nerve paralysis include an tracture, which occur relatively commonly in animals with

inability to close the eyelid, move the lip, or move the ear. long-standing facial nerve paralysis (Fig. 66.6). Many dogs