Page 35 - Gastrointestinal Bleeding (Xuất huyết tiêu hóa)

P. 35

CHAPTER 20 Gastrointestinal Bleeding 309

NSAID–Induced Small Intestinal Erosions and Ulcers Diagnostic Tests 20

Mucosal erosions or ulcers that can be seen on capsule endoscopy Imaging

develop in 25% to 55% of patients who take full-dose nonselec- Barium small bowel follow-through is no longer utilized because

tive NSAIDs. 344-348 Patients who take selective COX-2 inhibi- it has a low yield for determining the cause of obscure GI bleed-

tors have lower rates of mucosal ulcers on capsule endoscopy (see ing (with limited ability to distend the bowel and visualize

Chapter 119). mucosal lesions such as angiodysplasia). Barium studies are not

recommended for patients with acute bleeding; residual barium

Small Intestinal Neoplasms contrast in the GI tract can make urgent endoscopy, colonoscopy,

or angiography more difficult to perform.

Tumors of the small intestine comprise only 5% to 7% of all CT of the abdomen has the advantage of imaging extraluminal

GI tract neoplasms but are the most common cause of obscure structures as well as mucosal and intramural lesions in the small

GI bleeding in patients younger than age 50. 349 The most com- bowel. High-quality abdominal CT (with and without oral con-

mon small intestine neoplasms are adenomas (usually duodenal), trast) can show thickening of the small bowel, suggestive of Crohn

adenocarcinomas (Fig. 20.24), carcinoid tumors (usually ileal), disease or malignancy. Standard CT is less accurate than barium

GISTs, lymphomas, hamartomatosis polyps (Peutz-Jeghers syn- enteroclysis for the diagnosis of low-grade bowel obstruction,

drome), and juvenile polyps (see Chapters 32 to 34, 125, and 126). mucosal ulcerations, and fistulas. CT enteroclysis using a multi-

detector scanner provides better views of the small intestine than

Small Intestinal Diverticula standard CT. Because placement of a nasoduodenal tube is usually

required, patients sometimes receive moderate sedation for CT

The duodenum is the most common site of small intestinal diver- enteroclysis. 356 CT enterography with a high volume of an oral

ticula. In one large series, 350 79% of small intestinal diverticula contrast agent to distend the small bowel may have a diagnostic

occurred in the duodenum, 18% were in the jejunum or ileum, yield similar to that for CT enteroclysis, without the need for a

and only 3% were in all 3 segments—duodenum, jejunum, and nasoduodenal tube. MRI enteroclysis and enterography have also

ileum. Duodenal diverticula are noted in up to 20% of the pop- been described, but preliminary studies suggest that results to date

ulation, with an increasing frequency with age. 350-353 They are are inferior to those with a multidetector CT. MRI techniques

usually located along the medial wall of the second part of the duo- have the advantage of not exposing the patient to radiation.

denum within 1 to 2 cm of the ampulla of Vater. Bleeding from Nuclear medicine studies and angiography can be used to

a duodenal diverticulum is rare. Several reports have described evaluate obscure GI bleeding. A Meckel ( 99m Tc-pertechnetate)

bleeding from a duodenal diverticulum that was managed endo- scan can be useful for the diagnostic evaluation of a Meckel diver-

scopically. 353,354 Jejunal and ileal diverticula occur in 1% to 2% of ticulum, particularly in younger patients, as discussed earlier.

the population, are most commonly associated with scleroderma, Radionuclide scanning with technetium-labeled RBCs has lim-

another motility disorder, or SIBO, and only rarely have been ited utility because of its poor ability to localize the bleeding site

associated with bleeding (see Chapters 26, 37, and 105). in the small bowel. Angiography can be useful for patients with

active, acute small bowel bleeding because of the possibility of

Dieulafoy Lesion of the Small Intestine therapeutic embolization. Small case series have described pro-

vocative angiography, in which heparin or another anticoagulant

Several reports have described Dieulafoy lesions of the duode- is administered to provoke GI bleeding that has been intermit-

num, jejunum, and ileum (see Chapter 38). 355 Most affected per- tent. The technique increases the yield of detecting a bleeding

sons are younger than age 40, in contrast to those with gastric lesion but at the risk of causing a life-threatening complication. 357

Dieulafoy lesions, who tend to be older (see earlier). The lesions

are often challenging to find, and in the past were detected by Endoscopy

angiography and intraoperative endoscopy. Capsule endoscopy

can also localize and diagnose these lesions, which can be treated Push Enteroscopy

via a single- or double-balloon enteroscope. Push enteroscopy can be performed with a colonoscope (160 to

180 cm in length) or dedicated push enteroscope (220 to 250 cm in

length). 358 These endoscopes can be used to evaluate the esophagus,

stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum approximately 50 to

150 cm beyond the ligament of Treitz. Insertion is often limited by

looping of the endoscope in the stomach. Push enteroscopy identi-

fies a potential bleeding site in 50% or more patients, and roughly

50% of lesions found are within reach of a standard upper endo-

scope, suggesting that the lesion was missed or unrecognized on

the initial examination. 309,310,358 The overall diagnostic yield of push

enteroscopy is approximately 40%, with a range of 3% to 80% in

various studies; the most commonly detected lesions are angioecta-

sias. 309 In the UCLA CURE hemostasis experience in patients with

recurrent severe, obscure, overt GI bleeding manifesting as melena,

the diagnostic yield has been 80%. The lesions were categorized

57

as those missed by EGD, those in the duodenum (first to fourth

portion), and those in the jejunum; most lesions were within reach

of a push enteroscope. Focal lesions were treated endoscopically,

biopsied, or tattooed. Patients in whom a diagnosis was not made by

push enteroscopy underwent further studies (see Fig. 20.5).

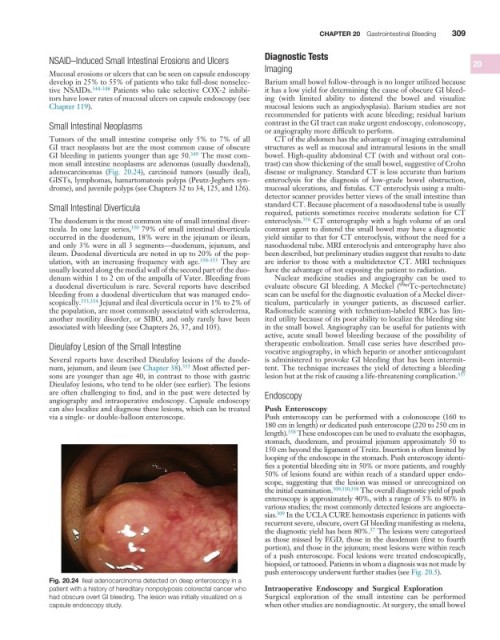

Fig. 20.24 Ileal adenocarcinoma detected on deep enteroscopy in a

patient with a history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer who Intraoperative Endoscopy and Surgical Exploration

had obscure overt GI bleeding. The lesion was initially visualized on a Surgical exploration of the small intestine can be performed

capsule endoscopy study. when other studies are nondiagnostic. At surgery, the small bowel