Page 557 - Atlas Sea Birds Ver1

P. 557

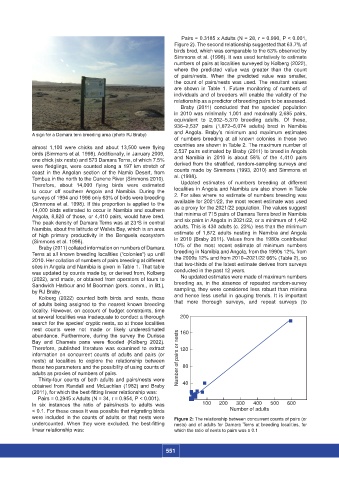

Pairs = 0.3185 x Adults (N = 28, r = 0.990, P < 0.001,

Figure 2). The second relationship suggested that 63.7% of

birds bred, which was comparable to the 63% observed by

Simmons et al. (1998). It was used tentatively to estimate

numbers of pairs at localities surveyed by Kolberg (2022),

where the predicted value was greater than the count

of pairs/nests. When the predicted value was smaller,

the count of pairs/nests was used. The resultant values

are shown in Table 1. Future monitoring of numbers of

individuals and of breeders will enable the validity of the

relationship as a predictor of breeding pairs to be assessed.

Braby (2011) concluded that the species’ population

in 2010 was minimally 1,001 and maximally 2,685 pairs,

equivalent to 2,002–5,370 breeding adults. Of these,

936–2,537 pairs (1,872–5,074 adults) bred in Namibia

A sign for a Damara tern breeding area (photo RJ Braby) and Angola. Braby’s minimum and maximum estimates

of numbers breeding at all known colonies in these two

almost 1,100 were chicks and about 13,500 were flying countries are shown in Table 2. The maximum number of

birds (Simmons et al. 1998). Additionally, in January 2009, 2,537 pairs estimated by Braby (2011) to breed in Angola

one chick (six nests) and 573 Damara Terns, of which 7.5% and Namibia in 2010 is about 58% of the 4,410 pairs

were fledglings, were counted along a 197 km stretch of derived from the stratified, random-sampling surveys and

coast in the Angolan section of the Namib Desert, from counts made by Simmons (1993, 2010) and Simmons et

Tombua in the north to the Cunene River (Simmons 2010). al. (1998).

Therefore, about 14,000 flying birds were estimated Updated estimates of numbers breeding at different

to occur off southern Angola and Namibia. During the localities in Angola and Namibia are also shown in Table

surveys of 1994 and 1996 only 63% of birds were breeding 2. For sites where no estimate of numbers breeding was

(Simmons et al. 1998). If this proportion is applied to the available for 2021/22, the most recent estimate was used

14,000 birds estimated to occur in Namibia and southern as a proxy for the 2021/22 population. The values suggest

Angola, 8,820 of those, or 4,410 pairs, would have bred. that minima of 715 pairs of Damara Terns bred in Namibia

The peak density of Damara Terns was at 23°S in central and six pairs in Angola in 2021/22, or a minimum of 1,442

Namibia, about the latitude of Walvis Bay, which is an area adults. This is 430 adults (c. 23%) less than the minimum

of high primary productivity in the Benguela ecosystem estimate of 1,872 adults nesting in Namibia and Angola

(Simmons et al. 1998). in 2010 (Braby 2011). Values from the 1980s contributed

Braby (2011) collated information on numbers of Damara 10% of the most recent estimate of minimum numbers

Terns at all known breeding localities (“colonies”) up until breeding in Namibia and Angola, from the 1990s 12%, from

2010. Her collation of numbers of pairs breeding at different the 2000s 12% and from 2010–2021/22 66% (Table 2), so

sites in Angola and Namibia is given in Table 1. That table that two-thirds of the latest estimate derives from surveys

was updated by counts made by, or derived from, Kolberg conducted in the past 12 years.

(2022), and made, or obtained from operators of tours to No updated estimates were made of maximum numbers

Sandwich Harbour and M Boorman (pers. comm., in litt.), breeding as, in the absence of repeated random-survey

by RJ Braby. sampling, they were considered less robust than minima

Kolberg (2022) counted both birds and nests, those and hence less useful in gauging trends. It is important

of adults being assigned to the nearest known breeding that more thorough surveys, and repeat surveys (to

locality. However, on account of budget constraints, time

at several localities was inadequate to conduct a thorough 200

search for the species’ cryptic nests, so at those localities

nest counts were not made or likely underestimated

abundance. Furthermore, during the survey the Durissa 160

Bay and Chameis pans were flooded (Kolberg 2022).

Therefore, published literature was examined to extract 120

information on concurrent counts of adults and pairs (or

nests) at localities to explore the relationship between Number of pairs or nests

these two parameters and the possibility of using counts of 80

adults as proxies of numbers of pairs.

Thirty-four counts of both adults and pairs/nests were

obtained from Randall and McLachlan (1982) and Braby 40

(2011), for which the best-fitting linear relationship was:

Pairs = 0.2945 x Adults (N = 34, r = 0.954, P < 0.001).

In six instances the ratio of pairs/nests to adults was 100 200 300 400 500 600

< 0.1. For these cases it was possible that migrating birds Number of adults

were included in the counts of adults or that nests were Figure 2: The relationship between concurrent counts of pairs (or

undercounted. When they were excluded, the best-fitting nests) and of adults for Damara Terns at breeding localities, for

linear relationship was: which the ratio of nests to pairs was ≥ 0.1

551