Page 19 - Ming_China_Courts_and_Contacts_1400_1450 Craig lunas

P. 19

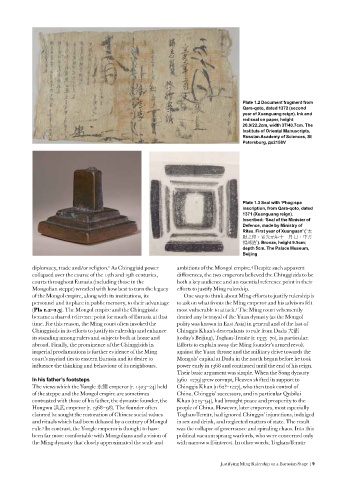

Plate 1.2 Document fragment from

Qara-qoto, dated 1372 (second

year of Xuanguang reign). Ink and

red seal on paper, height

20.9/22.2cm, width 37/40.7cm. The

Institute of Oriental Manuscripts,

Russian Academy of Sciences, St

Petersburg, дх2158V

Plate 1.3 Seal with ‘Phag-spa

inscription, from Qara-qoto, dated

1371 (Xuanguang reign).

Inscribed: ‘Seal of the Minister of

Defence, made by Ministry of

Rites. First year of Xuanguan’ ( ‘太

尉之印。宣光元年十一月 日,中書

禮部造’). Bronze, height 9.5cm;

depth 5cm. The Palace Museum,

Beijing

4

2

diplomacy, trade and/or religion. As Chinggisid power ambitions of the Mongol empire. Despite such apparent

collapsed over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, differences, the two emperors believed the Chinggisids to be

courts throughout Eurasia (including those in the both a key audience and an essential reference point in their

Mongolian steppe) wrestled with how best to turn the legacy efforts to justify Ming rulership.

of the Mongol empire, along with its institutions, its One way to think about Ming efforts to justify rulership is

personnel and its place in public memory, to their advantage to ask on what fronts the Ming emperor and his advisors felt

(Pls 1.2–1.3). The Mongol empire and the Chinggisids most vulnerable to attack. The Ming court vehemently

5

became a shared reference point for much of Eurasia at that denied any betrayal of the Yuan dynasty (as the Mongol

time. For this reason, the Ming court often invoked the polity was known in East Asia) in general and of the last of

Chinggisids in its efforts to justify its rulership and enhance Chinggis Khan’s descendants to rule from Dadu 大都

its standing among rulers and subjects both at home and (today’s Beijing), Toghan-Temür (r. 1333–70), in particular.

abroad. Finally, the prominence of the Chinggisids in Efforts to explain away the Ming founder’s armed revolt

imperial proclamations is further evidence of the Ming against the Yuan throne and the military drive towards the

court’s myriad ties to eastern Eurasia and its desire to Mongols’ capital at Dadu in the north began before he took

influence the thinking and behaviour of its neighbours. power early in 1368 and continued until the end of his reign.

Their basic argument was simple. When the Song dynasty

In his father’s footsteps (960–1279) grew corrupt, Heaven shifted its support to

The views which the Yongle 永樂 emperor (r. 1403–24) held Chinggis Khan (1162?–1227), who then took control of

of the steppe and the Mongol empire are sometimes China. Chinggis’ successors, and in particular Qubilai

contrasted with those of his father, the dynastic founder, the Khan (1215–94), had brought peace and prosperity to the

Hongwu 洪武 emperor (r. 1368–98). The founder often people of China. However, later emperors, most especially

claimed he sought the restoration of Chinese social values Toghan-Temür, had ignored Chinggis’ injunctions, indulged

and rituals which had been debased by a century of Mongol in sex and drink, and neglected matters of state. The result

rule. In contrast, the Yongle emperor is thought to have was the collapse of governance and spiraling chaos. Into this

3

been far more comfortable with Mongolians and a vision of political vacuum sprang warlords, who were concerned only

the Ming dynasty that closely approximated the scale and with narrow self-interest. In other words, Toghan-Temür

Justifying Ming Rulership on a Eurasian Stage | 9