Page 93 - Christies IMportant Chinese Art Sept 26 2020 NYC

P. 93

Shah Jahan ruled during what has been called the Golden Age, and alongside

his political, intellectual and other interests, he was a great patron of the

arts. He had an especial interest in architecture and ordered the building of

a significant number of spectacular monuments, the best known of which

is the Taj Mahal, which was built at Agra during the period AD 1632-48 as a

tomb for his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal, and where he too was eventually

buried. It would seem that Shah Jahan inherited his admiration of Chinese

porcelain from his father Jahangir, who held Chinese design in high esteem

and who, according to Sir Thomas Roe (AD 1581-1644), ‘prized china more

than gold and silver, horses and jewels’, and who reportedly almost beat

a man to death on one occasion because he had broken a piece of the

emperor’s beloved Chinese porcelain. Sir Thomas Roe was Ambassador to

the court at Agra from 1615 to 1618, and became something of a favourite

of Emperor Jahangir. His diaries are a valuable source of information on the

Mughal court of the early 17th century. A number of Chinese porcelains are

known which are inscribed with the name of Shah Jahan, his father Jahangir,

or his successor Aurangzeb (r. AD 1658-1707). It has been suggested that

such inscriptions were applied on the orders of the emperors themselves as

marks of ownership or lineage, or that they were inscribed as gifts from the

Persian or Turkish royal houses. A large mid-14th century blue and white dish

and a large late 14th or early 15th century white dish from the Rockefeller

Collection both bear inscriptions naming Shah Jahan (see Asia Society,

Imperial Elegance – Chinese Ceramics from the Asia Society’s Rockefeller

Collection, New York, 2005). A dish of similar shape to the current vessel,

but of slightly larger size and with a grape motif in the central panel, was

sold by Sotheby’s New York on 18th March 2015, lot 264. The New York dish

also bears the mark of ownership of the 17th century Mughal emperor Shah

Jahan, written in a fine nasta liq script. This latter inscription includes the

date 1053 AH, which corresponds to AD 1644. Shah Jahan clearly passed

on his enthusiasm for these Chinese blue and white dishes to his son, since

the al-Sabah Collection contains a similar dish, although with grapes in the

central panel, which is inscribed under the rim Alangir Shahi 1071, 3, denoting

the third regnal year of Shah Jahan’s son Aurangzeb - the date equivalent to

AD 1660 (see O. Watson, Ceramics from Islamic Lands, London, 2004, pp.

484-6, no. W1).

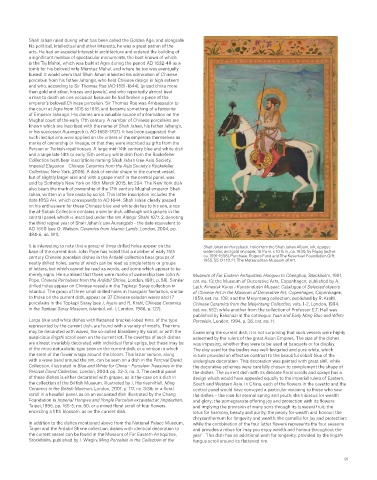

It is interesting to note that a group of three drilled holes appear on the Shah Jahan on Horseback, Folio from the Shah Jahan Album, ink, opaque

base of the current dish. John Pope has noted that a number of early 15th watercolor, and gold on paper, 15 5/16 in. x 10 1/8 in., ca. 1630, by Payag (active

century Chinese porcelain dishes in the Ardabil collection bear groups of ca. 1591-1658), Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift,

1955, 55.121.10.21, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

neatly drilled holes, some of which can be read as single letters or groups

of letters, but which cannot be read as words, and some which appear to be

merely signs. He surmised that these were marks of ownership (see John A. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities: Hongwu to Chenghua, Stockholm, 1991,

Pope, Chinese Porcelains from the Ardebil Shrine, London, 1981, p. 58). Similar cat. no. 13; the Museum of Decorative Arts, Copenhagen, published by A.

drilled holes appear on Chinese vessels in the Topkapi Saray collection in Leth, Kinesisk Kunst i Kunstindustri Museet: Catalogue of Selected objects

Istanbul. The group of three small drilled holes in triangular formation, similar of Chinese Art in the Museum of Decorative Art, Copenhagen, Copenhagen,

to those on the current dish, appear on 37 Chinese celadon wares and 17 1959, cat. no. 108; and the Meiyintang collection, published by R. Krahl,

porcelains in the Topkapi Saray (see J. Ayers and R. Krahl, Chinese Ceramics Chinese Ceramics from the Meiyintang Collection, vols. 1-2, London, 1994,

in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, vol. I, London, 1986, p. 127). cat. no. 662; while another from the collection of Professor E.T. Hall was

published by Eskenazi in the catalogue Yuan and Early Ming Blue and White

Large blue and white dishes with flattened bracket-lobed rims, of the type Porcelain, London, 1994, p. 36, cat. no. 11.

represented by the current dish, are found with a variety of motifs. The rims

may be decorated with waves, the so-called blackberry lily scroll, or with the Examining the current dish, it is not surprising that such vessels were highly

auspicious lingzhi scroll seen on the current lot. The cavettos of such dishes esteemed by the rulers of the great Asian Empires. The size of the dishes

are almost invariably decorated with individual floral sprigs, but these may be was imposing, whether they were to be used at banquets or for display.

of the more naturalistic type seen on the current dish, or a version in which The clay used for the bodies was well-levigated and pure white, which

the stem of the flower wraps around the bloom. This latter version, along in turn provided an effective contrast to the beautiful cobalt blue of the

with a wave band around the rim, can be seen on a dish in the Percival David underglaze decoration. This decoration was painted with great skill, while

Collection, illustrated in Blue and White for China – Porcelain Treasures in the the decorative schemes were carefully chosen to complement the shape of

Percival David Collection, London, 2004, pp. 22-3, no. 3. The central panel the dishes. The current dish with its delicate floral scrolls and sprays has a

of these dishes is either decorated with grapes, as is the case on a dish in design which would have appealed equally to the imperial rulers of Eastern,

the collection of the British Museum, illustrated by J. Harrison-Hall, Ming South and Western Asia. In China, each of the flowers in the cavetto and the

Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, p. 117, no. 3:36; or a floral central panel would have conveyed a particular meaning to those who saw

scroll in a hexafoil panel, as on an excavated dish illustrated by the Chang the dishes – the rose for eternal spring and youth; the hibiscus for wealth

Foundation in Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen, and glory; the pomegranate offering joy and protection with its flowers

Taipei, 1996, pp. 165-5, no. 50; or a mixed floral scroll of four flowers and implying the provision of many sons through its (unseen) fruit; the

encircling a fifth blossom, as on the current dish. lotus for harmony, beauty and purity; the peony for wealth and honour; the

chrysanthemum for longevity and wealth; the camellia for joy and protection;

In addition to the dishes mentioned above from the National Palace Museum, while the combination of the four latter flowers represents the four seasons

Taipei and the Ardabil Shrine collection, dishes with identical decoration to and provides a rebus for ‘may you enjoy wealth and honour throughout the

the current vessel can be found in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, year’ . This dish has an additional wish for longevity, provided by the lingzhi

Stockholm, published by J. Wirgin, Ming Porcelain in the Collection of the fungus scroll around its flattened rim.

91