Page 335 - American Stories, A History of the United States

P. 335

The essential features of the emerging mode

13.1 of production were gathering a supervised work-

force in a single place, paying cash wages to work-

ers, using interchangeable parts, and manufacturing

BRITISH NORTH AMERICA

13.2 (CANADA) by “continuous process.” Within a factory setting,

a sequence of continuous operations could rapidly

and efficiently assemble standardized parts, manu-

Boston factured separately and in bulk, into a final product.

Great Lakes

Mass production, which involved the division of

Detroit labor into a series of relatively simple and repetitive

New York

Pittsburgh tasks, contrasted sharply with the traditional craft

Philadelphia mode of production, in which a single worker pro-

Chicago

Washington, D.C. duced the entire product out of raw materials.

The transition to mass production often

St. Cincinnati depended on new technology. Just as power looms

Joseph

and spinning machinery had made textile mills

St. Louis possible, new and more reliable machines or indus-

ATLANTIC

OCEAN trial techniques revolutionized other industries.

Charleston Elias Howe’s invention of the sewing machine in

1846 laid the basis for the ready-to-wear clothing

industry and contributed to the mechanization of

shoemaking. During the 1840s, iron manufactur-

ers adopted the British practice of using coal rather

New Orleans than charcoal for smelting and thus produced a

Houston

metal better suited to industrial needs. Charles

Goodyear’s discovery in 1839 of the process for

Gulf of Mexico

vulcanizing rubber made new manufactured items

Railroads available to the American consumer, most notably

in 1850

0 200 400 miles Railroads built the overshoe.

between 1850 Perhaps the greatest triumph of mid-

0 200 400 kilometers and 1860

nineteenth-century American technology was the

development of the world’s most sophisticated

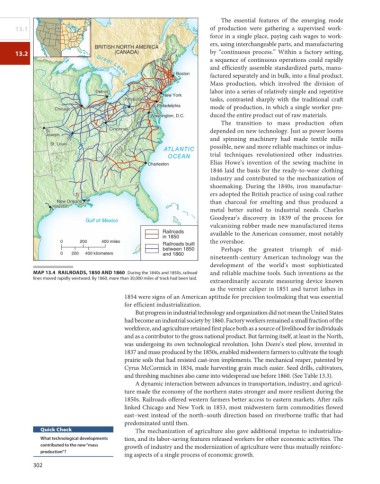

mAP 13.4 RAilRoAdS, 1850 And 1860 During the 1840s and 1850s, railroad and reliable machine tools. Such inventions as the

lines moved rapidly westward. by 1860, more than 30,000 miles of track had been laid.

extraordinarily accurate measuring device known

as the vernier caliper in 1851 and turret lathes in

1854 were signs of an American aptitude for precision toolmaking that was essential

for efficient industrialization.

But progress in industrial technology and organization did not mean the United States

had become an industrial society by 1860. Factory workers remained a small fraction of the

workforce, and agriculture retained first place both as a source of livelihood for individuals

and as a contributor to the gross national product. But farming itself, at least in the North,

was undergoing its own technological revolution. John Deere’s steel plow, invented in

1837 and mass produced by the 1850s, enabled midwestern farmers to cultivate the tough

prairie soils that had resisted cast-iron implements. The mechanical reaper, patented by

Cyrus McCormick in 1834, made harvesting grain much easier. Seed drills, cultivators,

and threshing machines also came into widespread use before 1860. (See Table 13.3).

A dynamic interaction between advances in transportation, industry, and agricul-

ture made the economy of the northern states stronger and more resilient during the

1850s. Railroads offered western farmers better access to eastern markets. After rails

linked Chicago and New York in 1853, most midwestern farm commodities flowed

east–west instead of the north–south direction based on riverborne traffic that had

predominated until then.

Quick Check The mechanization of agriculture also gave additional impetus to industrializa-

What technological developments tion, and its labor-saving features released workers for other economic activities. The

contributed to the new “mass growth of industry and the modernization of agriculture were thus mutually reinforc-

production”?

ing aspects of a single process of economic growth.

302