Page 337 - American Stories, A History of the United States

P. 337

Mass immigration begins

13.1 The incentive to mechanize northern industry and agriculture came in part from a

shortage of cheap labor. Compared to the industrializing nations of Europe, the econ-

omy of the United States in the early nineteenth century was labor-scarce. Since it was

13.2 difficult to attract able-bodied men to work for low wages in factories or on farms,

women and children were used extensively in the early textile mills, and commercial

farmers had to rely on the labor of their family members. Labor-saving machinery

eased but did not solve the labor shortage. Factories required more operatives. Railroad

builders needed construction gangs. The growth of industrial work attracted many

European immigrants during the two decades before the Civil War.

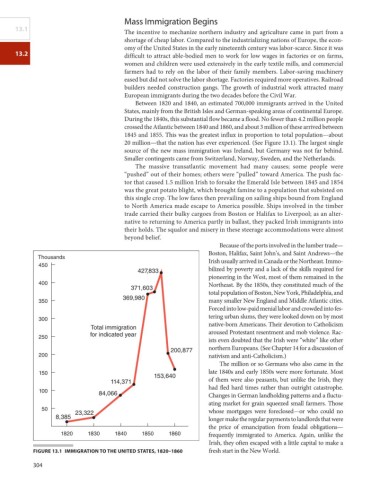

Between 1820 and 1840, an estimated 700,000 immigrants arrived in the United

States, mainly from the British Isles and German-speaking areas of continental Europe.

During the 1840s, this substantial flow became a flood. No fewer than 4.2 million people

crossed the Atlantic between 1840 and 1860, and about 3 million of these arrived between

1845 and 1855. This was the greatest influx in proportion to total population—about

20 million—that the nation has ever experienced. (See Figure 13.1). The largest single

source of the new mass immigration was Ireland, but Germany was not far behind.

Smaller contingents came from Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands.

The massive transatlantic movement had many causes; some people were

“pushed” out of their homes; others were “pulled” toward America. The push fac-

tor that caused 1.5 million Irish to forsake the Emerald Isle between 1845 and 1854

was the great potato blight, which brought famine to a population that subsisted on

this single crop. The low fares then prevailing on sailing ships bound from England

to North America made escape to America possible. Ships involved in the timber

trade carried their bulky cargoes from Boston or Halifax to Liverpool; as an alter-

native to returning to America partly in ballast, they packed Irish immigrants into

their holds. The squalor and misery in these steerage accommodations were almost

beyond belief.

Because of the ports involved in the lumber trade—

Boston, Halifax, Saint John’s, and Saint Andrews—the

Thousands Irish usually arrived in Canada or the Northeast. Immo-

450

427,833 bilized by poverty and a lack of the skills required for

pioneering in the West, most of them remained in the

400 Northeast. By the 1850s, they constituted much of the

371,603

total population of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and

369,980

350 many smaller New England and Middle Atlantic cities.

Forced into low-paid menial labor and crowded into fes-

tering urban slums, they were looked down on by most

300

Total immigration native-born Americans. Their devotion to Catholicism

250 for indicated year aroused Protestant resentment and mob violence. Rac-

ists even doubted that the Irish were “white” like other

200,877 northern Europeans. (See Chapter 14 for a discussion of

200 nativism and anti-Catholicism.)

The million or so Germans who also came in the

150 153,640 late 1840s and early 1850s were more fortunate. Most

114,371 of them were also peasants, but unlike the Irish, they

100 84,066 had fled hard times rather than outright catastrophe.

Changes in German landholding patterns and a fluctu-

ating market for grain squeezed small farmers. Those

50 23,322 whose mortgages were foreclosed—or who could no

8,385 longer make the regular payments to landlords that were

the price of emancipation from feudal obligations—

1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 frequently immigrated to America. Again, unlike the

Irish, they often escaped with a little capital to make a

fiGURe 13.1 immiGRAtion to tHe United StAteS, 1820–1860 fresh start in the New World.

304