Page 361 - American Stories, A History of the United States

P. 361

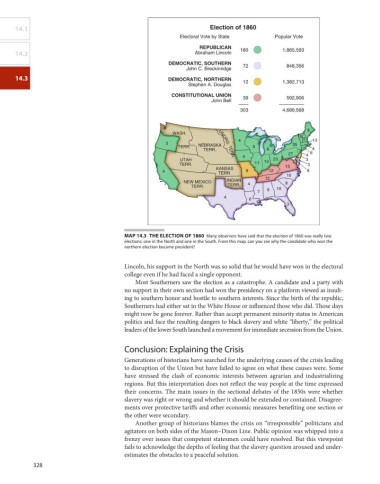

14.1 Election of 1860

Electoral Vote by State Popular Vote

REPUBLICAN

14.2 Abraham Lincoln 180 1,865,593

DEMOCRATIC, SOUTHERN

John C. Breckinridge 72 848,356

14.3 DEMOCRATIC, NORTHERN

Stephen A. Douglas 12 1,382,713

CONSTITUTIONAL UNION 39 592,906

John Bell

303 4,689,568

8

WASH.

5

4 5 13

3 NEBRASKA 35

TERR. UNORG. TERR. 5

TERR. 6 6 4

4 27 4

UTAH 13 23 3

TERR. 11 15 3

KANSAS

4 TERR. 9 12 8

12 10

NEW MEXICO INDIAN 4 8

TERR. TERR. 10

7 9

4 6

3

MAp 14.3 tHe eLeCtioN oF 1860 Many observers have said that the election of 1860 was really two

elections: one in the North and one in the South. From this map, can you see why the candidate who won the

northern election became president?

Lincoln, his support in the North was so solid that he would have won in the electoral

college even if he had faced a single opponent.

Most Southerners saw the election as a catastrophe. A candidate and a party with

no support in their own section had won the presidency on a platform viewed as insult-

ing to southern honor and hostile to southern interests. Since the birth of the republic,

Southerners had either sat in the White House or influenced those who did. Those days

might now be gone forever. Rather than accept permanent minority status in American

politics and face the resulting dangers to black slavery and white “liberty,” the political

leaders of the lower South launched a movement for immediate secession from the Union.

Conclusion: explaining the Crisis

Generations of historians have searched for the underlying causes of the crisis leading

to disruption of the Union but have failed to agree on what these causes were. Some

have stressed the clash of economic interests between agrarian and industrializing

regions. But this interpretation does not reflect the way people at the time expressed

their concerns. The main issues in the sectional debates of the 1850s were whether

slavery was right or wrong and whether it should be extended or contained. Disagree-

ments over protective tariffs and other economic measures benefiting one section or

the other were secondary.

Another group of historians blames the crisis on “irresponsible” politicians and

agitators on both sides of the Mason–Dixon Line. Public opinion was whipped into a

frenzy over issues that competent statesmen could have resolved. But this viewpoint

fails to acknowledge the depths of feeling that the slavery question aroused and under-

estimates the obstacles to a peaceful solution.

328