Page 247 - Ming_China_Courts_and_Contacts_1400_1450 Craig lunas

P. 247

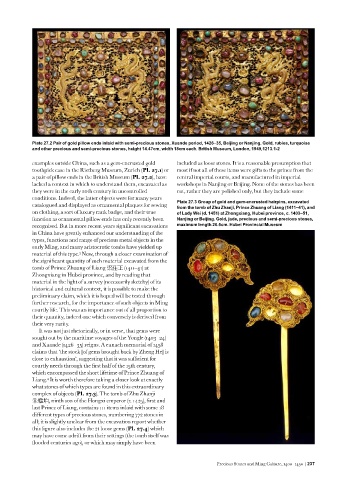

Plate 27.2 Pair of gold pillow ends inlaid with semi-precious stones, Xuande period, 1426–35, Beijing or Nanjing. Gold, rubies, turquoise

and other precious and semi-precious stones, height 14.47cm, width 18cm each. British Museum, London, 1949,1213.1-2

examples outside China, such as a gem-encrusted gold included as loose stones. It is a reasonable presumption that

toothpick case in the Rietberg Museum, Zurich (Pl. 27.1) or most if not all of these items were gifts to the prince from the

a pair of pillow ends in the British Museum (Pl. 27.2), have central imperial courts, and manufactured in imperial

lacked a context in which to understand them, excavated as workshops in Nanjing or Beijing. None of the stones has been

they were in the early 20th century in uncontrolled cut, rather they are polished only, but they include some

conditions. Indeed, the latter objects were for many years

catalogued and displayed as ornamental plaques for sewing Plate 27.3 Group of gold and gem-encrusted hairpins, excavated

from the tomb of Zhu Zhanji, Prince Zhuang of Liang (1411–41), and

on clothing, a sort of luxury rank badge, and their true of Lady Wei (d. 1451) at Zhongxiang, Hubei province, c. 1403–51,

function as ornamental pillow ends has only recently been Nanjing or Beijing. Gold, jade, precious and semi-precious stones,

recognised. But in more recent years significant excavations maximum length 20.5cm. Hubei Provincial Museum

in China have greatly enhanced our understanding of the

types, functions and range of precious metal objects in the

early Ming, and many aristocratic tombs have yielded up

material of this type. Now, through a closer examination of

3

the significant quantity of such material excavated from the

tomb of Prince Zhuang of Liang 梁莊王 (1411–41) at

Zhongxiang in Hubei province, and by reading that

material in the light of a survey (necessarily sketchy) of its

historical and cultural context, it is possible to make the

preliminary claim, which it is hoped will be tested through

further research, for the importance of such objects in Ming

courtly life. This was an importance out of all proportion to

their quantity, indeed one which conversely is derived from

their very rarity.

It was not just rhetorically, or in verse, that gems were

sought out by the maritime voyages of the Yongle (1403–24)

and Xuande (1426–35) reigns. A eunuch memorial of 1458

claims that ‘the stock [of gems brought back by Zheng He] is

close to exhaustion’, suggesting that it was sufficient for

courtly needs through the first half of the 15th century,

which encompassed the short lifetime of Prince Zhuang of

4

Liang. It is worth therefore taking a closer look at exactly

what stones of which types are found in this extraordinary

complex of objects (Pl. 27.3). The tomb of Zhu Zhanji

朱瞻垍, ninth son of the Hongxi emperor (r. 1425), first and

last Prince of Liang, contains 111 items inlaid with some 18

different types of precious stones, numbering 772 stones in

all; it is slightly unclear from the excavation report whether

this figure also includes the 21 loose gems (Pl. 27.4) which

may have come adrift from their settings (the tomb itself was

flooded centuries ago), or which may simply have been

Precious Stones and Ming Culture, 1400–1450 | 237