Page 34 - Sotheby's Qianlong Calligraphy Oct. 3, 2018

P. 34

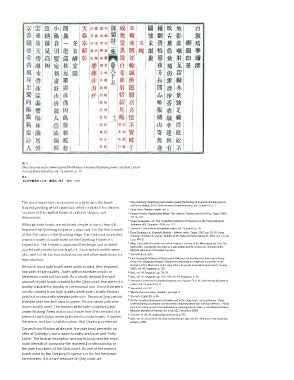

fig. 5

Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of imperial Qianlong poems and text], Yuzhi

shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18

圖五

《清高宗御製詩文全集.御製詩二集》,卷65,頁18

The most important component in a lathe was the bowl- 1 Qing Gaozong (Qianlong) yuzhi shiwen quanji [Anthology of Imperial Qianlong poems

and text], Beijing, 1993, Yuzhi shi san ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 3], juan 53, p. 2.

shaped grinding wheel (wantuo), which enabled the efficient 2 Yang Shen, Danqian zonglu, vol. 3.

creation of thin-walled bowls of uniform shapes and 3 Empty Vessels, Replenished Minds. The Culture, Practice and Art of Tea, Taipei, 2002,

dimensions. cat. no. 165.

4 Zhang Guangwen, ed., The Complete Collection of Treasures in the Palace Museum.

Although jade bowls are relatively simple in form, they still Jadeware (III), Shanghai, 2008, no. 223.

required the Qianlong Emperor’s approval. On the third month 5 See note 1, Yuzhi shi er ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 2], juan 65, p. 18.

of the 25th year of the Qianlong reign, the Zaobanchu created 6 Deng Shuping, ed., Exquisite Beauty – Islamic Jades, Taipei, 2007, pp. 28-30. Deng

Shuping, ‘Xiangfei de yuwan’, Bulletin of the National Palace Museum, 1983, vol. 1, issue

a wood model of a jade bowl for the Qianlong Emperor’s 1, pp. 88-92.

inspection. The Emperor approved the design and ordered 7 Ming Taizu shilu [Veritable records of Emperor Taizong of the Ming dynasty]. Here the

jade bowl is mistakenly recorded as a jade pillow, but the section on Chengzu in the

a jade bowl created according to it. Such wood models were Mingshi [Historian of the Ming dynasty].

also sent to the Suzhou manufactory and other workshops for 8 See note 4, no. 220.

reproduction. 9 First Historical Archives of China and Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong

Kong, eds, Qinggong Neiwufu Zaobanchu huoji dang’an zonghui [Documents in the

Because most jade bowls were undecorated, they required Archives of the Workshop of the Qing Palace Imperial Household Department], Beijing,

2005, vol. 42, Ruyiguan, p. 716.

raw jade of high quality. Jades with noticeable cracks or 10 Ibid., vol. 44, Ruyiguan, pp. 38-39.

blemishes could not be used. As a result, despite the vast 11 Ibid., vol. 42, Ruyiguan, pp. 708-709; vol. 44, Ruyiguan, p. 48.

amount of jade bowls created by the Qing court, few were of a 12 See note 1, Yuzhi shi si ji [Imperial poetry, vol. 4], juan 31, p. 18; Yuzhi shi wu ji [Imperial

poetry, vol. 5], juan 23, p. 8.

quality suitable for display or ceremonial use. Those that were 13 See note 4, no. 217.

mostly created from high-quality white jade, usually Khotan 14 ‘Waichushuozuoshang’, Hanfeizi, passage 32.

jade but occasionally shanliao jade also. Because Qing-period 15 See note 1, juan 98, p. 34.

shanliao jade tended towards green, Khotan white jade was 16 On the standard dimensions of bowls used in the Qing court, see Liao Baoxiu, ‘Cong

sede huafalang yu yangcai ciqi tan wenwu dingming wenti [On naming artefacts: a study

more usually used. The famous white jade sculpture Lady based on colour-ground enamelled wares and yangcai porcelains]’, The National Palace

under Wutong Trees was in fact made from the remnant of a Museum Monthly of Chinese Art, issue 321, December 2009.

17 See note 9, vol. 30, xingwen [general text], p. 772.

piece of raw Khotan white jade used to make bowls. It typifies 18 Ibid., vol. 42, Records of the imperial workshops dated to the 44th year of the Qianlong

the warm, mutton-fat white colour that Qianlong preferred. period, p. 666.

Carved from Khotan white jade, the jade bowl presently on

offer at Sotheby’s has a warm tonality and pure and “fatty”

lustre. The textual inscription around its body and the reign

mark beneath it showcase the masterful craftsmanship of

the jade inscribers of the Qing court. As one of the earliest

bowls used by the Qianlong Emperor’s in his tea-bestowal

ceremonies, it is a rare treasure of Qing court art.