Page 75 - EALC C306/505

P. 75

67

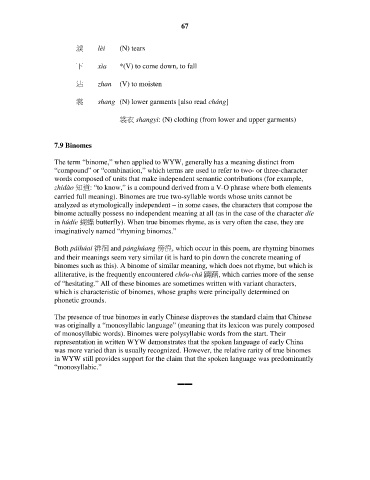

淚 lèi (N) tears

下 xìa *(V) to come down, to fall

沾 zhan (V) to moisten

裳 shang (N) lower garments [also read cháng]

裳衣 shangyi: (N) clothing (from lower and upper garments)

7.9 Binomes

The term “binome,” when applied to WYW, generally has a meaning distinct from

“compound” or “combination,” which terms are used to refer to two- or three-character

words composed of units that make independent semantic contributions (for example,

zhidào 知道: “to know,” is a compound derived from a V-O phrase where both elements

carried full meaning). Binomes are true two-syllable words whose units cannot be

analyzed as etymologically independent – in some cases, the characters that compose the

binome actually possess no independent meaning at all (as in the case of the character díe

in húdíe 蝴蝶 butterfly). When true binomes rhyme, as is very often the case, they are

imaginatively named “rhyming binomes.”

Both páihúai 徘徊 and pánghúang 傍徨, which occur in this poem, are rhyming binomes

and their meanings seem very similar (it is hard to pin down the concrete meaning of

binomes such as this). A binome of similar meaning, which does not rhyme, but which is

alliterative, is the frequently encountered chóu-chú 躊躇, which carries more of the sense

of “hesitating.” All of these binomes are sometimes written with variant characters,

which is characteristic of binomes, whose graphs were principally determined on

phonetic grounds.

The presence of true binomes in early Chinese disproves the standard claim that Chinese

was originally a “monosyllabic language” (meaning that its lexicon was purely composed

of monosyllabic words). Binomes were polysyllabic words from the start. Their

representation in written WYW demonstrates that the spoken language of early China

was more varied than is usually recognized. However, the relative rarity of true binomes

in WYW still provides support for the claim that the spoken language was predominantly

“monosyllabic.”

▬▬