Page 145 - Essentials of Human Communication

P. 145

124 ChAPTeR 6 Interpersonal Communication and Conversation

Turn-Maintaining Cues. Through turn-maintaining cues you can

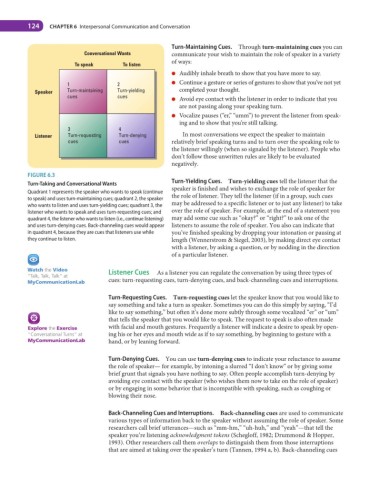

Conversational Wants communicate your wish to maintain the role of speaker in a variety

of ways:

To speak To listen

● Audibly inhale breath to show that you have more to say.

1 2 ● Continue a gesture or series of gestures to show that you’ve not yet

Speaker Turn-maintaining Turn-yielding completed your thought.

cues cues ● Avoid eye contact with the listener in order to indicate that you

are not passing along your speaking turn.

● Vocalize pauses (“er,” “umm”) to prevent the listener from speak-

ing and to show that you’re still talking.

3 4

Listener Turn-requesting Turn-denying In most conversations we expect the speaker to maintain

cues cues relatively brief speaking turns and to turn over the speaking role to

the listener willingly (when so signaled by the listener). People who

don’t follow those unwritten rules are likely to be evaluated

negatively.

Figure 6.3

Turn-Taking and Conversational Wants Turn-Yielding Cues. Turn-yielding cues tell the listener that the

Quadrant 1 represents the speaker who wants to speak (continue speaker is finished and wishes to exchange the role of speaker for

to speak) and uses turn-maintaining cues; quadrant 2, the speaker the role of listener. They tell the listener (if in a group, such cues

who wants to listen and uses turn-yielding cues; quadrant 3, the may be addressed to a specific listener or to just any listener) to take

listener who wants to speak and uses turn-requesting cues; and over the role of speaker. For example, at the end of a statement you

quadrant 4, the listener who wants to listen (i.e., continue listening) may add some cue such as “okay?” or “right?” to ask one of the

and uses turn-denying cues. Back-channeling cues would appear listeners to assume the role of speaker. You also can indicate that

in quadrant 4, because they are cues that listeners use while you’ve finished speaking by dropping your intonation or pausing at

they continue to listen. length (Wennerstrom & Siegel, 2003), by making direct eye contact

with a listener, by asking a question, or by nodding in the direction

of a particular listener.

Watch the Video listener Cues As a listener you can regulate the conversation by using three types of

“Talk, Talk, Talk” at

MyCommunicationLab cues: turn-requesting cues, turn-denying cues, and back-channeling cues and interruptions.

Turn-requesting Cues. Turn-requesting cues let the speaker know that you would like to

say something and take a turn as speaker. Sometimes you can do this simply by saying, “I’d

like to say something,” but often it’s done more subtly through some vocalized “er” or “um”

that tells the speaker that you would like to speak. The request to speak is also often made

Explore the Exercise with facial and mouth gestures. Frequently a listener will indicate a desire to speak by open-

“Conversational Turns” at ing his or her eyes and mouth wide as if to say something, by beginning to gesture with a

MyCommunicationLab hand, or by leaning forward.

Turn-Denying Cues. You can use turn-denying cues to indicate your reluctance to assume

the role of speaker— for example, by intoning a slurred “I don’t know” or by giving some

brief grunt that signals you have nothing to say. Often people accomplish turn-denying by

avoiding eye contact with the speaker (who wishes them now to take on the role of speaker)

or by engaging in some behavior that is incompatible with speaking, such as coughing or

blowing their nose.

Back-Channeling Cues and interruptions. Back-channeling cues are used to communicate

various types of information back to the speaker without assuming the role of speaker. Some

researchers call brief utterances—such as “mm-hm,” “uh-huh,” and “yeah”—that tell the

speaker you’re listening acknowledgment tokens (Schegloff, 1982; Drummond & Hopper,

1993). Other researchers call them overlaps to distinguish them from those interruptions

that are aimed at taking over the speaker’s turn (Tannen, 1994 a, b). Back-channeling cues