Page 775 - Adams and Stashak's Lameness in Horses, 7th Edition

P. 775

Lameness of the Proximal Limb 741

the affected limb may be higher than the hock on the

normal limb, with some degree of external rotation of

VetBooks.ir any swelling present and may appear to bear weight on

the limb (Figure 5.142). Often the horse will not have

the limb, but often will not completely load the heel. If

the fracture is several days old, swelling may be palpated

on the medial aspect of the thigh. Palpation (± ausculta-

tion) over the greater trochanter while the limb is being

manipulated may reveal crepitus. If the horse is large

enough, a rectal exam may reveal subtle crepitation

when the limb is manipulated.

Although physical exam findings may suffice to diag-

nose a femoral fracture, radiographs are important to

make a definitive diagnosis and demonstrate the exact

location and configuration of the fracture such that

treatment and prognosis can be determined. For the dis-

tal one‐third of the femur, standing views will usually

identify the fracture, but for the proximal two‐thirds of

the femur, particularly in adults, a recumbent position is

required to obtain quality radiographs (Figure 5.143).

The most useful radiograph of the proximal two‐thirds

of the femur is taken medial to lateral with the horse in

dorsal recumbency but tipped onto the injured limb

(Figure 5.143B). Adequate penetration is difficult for the

cranial to caudal projection, but the image may still be

useful. A standing view of the proximal femur/coxofem-

oral region may suffice in certain cases. Digital radiog-

56

raphy has significantly facilitated acquisition of quality

images of this region, and standing oblique projections

of the femoral shaft may demonstrate a lesion almost as

well as in an anesthetized horse. The quality of the

images often depends on the size of the horse and swell-

ing present; as both increase, the quality will decrease.

The suspected gravity of the injury and the anticipated

ability for the horse to recover from general anesthesia

without further injury must be considered.

Ultrasound may demonstrate cortical disruption to

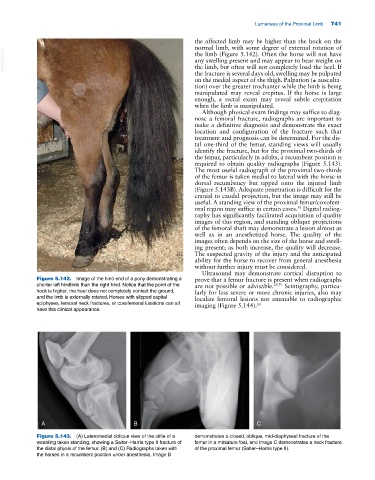

Figure 5.142. Image of the hind end of a pony demonstrating a prove that a femur fracture is present when radiographs

shorter left hindlimb than the right hind. Notice that the point of the are not possible or advisable. 29,71 Scintigraphy, particu-

hock is higher, the heel does not completely contact the ground, larly for less severe or more chronic injuries, also may

and the limb is externally rotated. Horses with slipped capital localize femoral lesions not amenable to radiographic

epiphyses, femoral neck fractures, or coxofemoral luxations can all imaging (Figure 5.144). 83

have this clinical appearance.

A B C

Figure 5.143. (A) Lateromedial oblique view of the stifle of a demonstrates a closed, oblique, mid‐diaphyseal fracture of the

weanling taken standing, showing a Salter–Harris type II fracture of femur in a miniature foal, and image C demonstrates a neck fracture

the distal physis of the femur. (B) and (C) Radiographs taken with of the proximal femur (Salter–Harris type II).

the horses in a recumbent position under anesthesia. Image B